Top Related Projects

A modern, C++-native, test framework for unit-tests, TDD and BDD - using C++14, C++17 and later (C++11 support is in v2.x branch, and C++03 on the Catch1.x branch)

GoogleTest - Google Testing and Mocking Framework

A modern, C++-native, test framework for unit-tests, TDD and BDD - using C++14, C++17 and later (C++11 support is in v2.x branch, and C++03 on the Catch1.x branch)

The fastest feature-rich C++11/14/17/20/23 single-header testing framework

A modern formatting library

Quick Overview

Boost.UT is a lightweight, single-header C++20 unit testing framework. It offers a simple and expressive syntax for writing tests, with a focus on compile-time performance and minimal runtime overhead. The framework is designed to be easy to use and integrate into existing projects.

Pros

- Single-header library, easy to integrate into projects

- Modern C++20 syntax, making tests concise and readable

- Fast compile times and minimal runtime overhead

- Supports various testing styles (BDD, TDD, and data-driven testing)

Cons

- Requires C++20 support, which may not be available in all environments

- Limited documentation compared to more established testing frameworks

- Smaller community and ecosystem compared to larger testing frameworks

- May have a steeper learning curve for developers unfamiliar with modern C++ features

Code Examples

- Basic test case:

#include <boost/ut.hpp>

int main() {

using namespace boost::ut;

"addition"_test = [] {

expect(1 + 2 == 3_i);

};

return 0;

}

- Parameterized test:

#include <boost/ut.hpp>

int main() {

using namespace boost::ut;

"multiplication"_test = [](auto num) {

expect(num * 2 == 2_i * num);

} | std::vector{1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

return 0;

}

- BDD-style test:

#include <boost/ut.hpp>

int main() {

using namespace boost::ut;

"calculator"_test = [] {

given("a calculator") = [] {

when("adding two numbers") = [] {

then("it should return the sum") = [] {

expect(2_i + 2_i == 4_i);

};

};

};

};

return 0;

}

Getting Started

To use Boost.UT in your project:

- Download the

ut.hppheader file from the GitHub repository. - Include the header in your test file:

#include "ut.hpp"

int main() {

using namespace boost::ut;

"my first test"_test = [] {

expect(true);

};

return 0;

}

- Compile your test file with C++20 support (e.g.,

g++ -std=c++20 test.cpp).

Competitor Comparisons

A modern, C++-native, test framework for unit-tests, TDD and BDD - using C++14, C++17 and later (C++11 support is in v2.x branch, and C++03 on the Catch1.x branch)

Pros of Catch2

- More mature and widely adopted in the C++ community

- Extensive documentation and examples available

- Supports a broader range of test types and scenarios

Cons of Catch2

- Slower compilation times, especially for large test suites

- More complex setup and configuration required

- Larger binary size due to its comprehensive feature set

Code Comparison

Catch2:

#define CATCH_CONFIG_MAIN

#include <catch2/catch.hpp>

TEST_CASE("Addition works") {

REQUIRE(1 + 1 == 2);

}

ut:

#include <boost/ut.hpp>

int main() {

using namespace boost::ut;

"Addition works"_test = [] { expect(1 + 1 == 2); };

}

Summary

Catch2 is a more established and feature-rich testing framework, offering comprehensive documentation and support for various testing scenarios. However, it comes with longer compilation times and a more complex setup. ut, on the other hand, provides a lightweight and header-only alternative with faster compilation times and a simpler syntax. The choice between the two depends on project requirements, team familiarity, and performance considerations.

GoogleTest - Google Testing and Mocking Framework

Pros of googletest

- More mature and widely adopted in the C++ community

- Extensive documentation and community support

- Supports a broader range of testing features and assertions

Cons of googletest

- Larger codebase and slower compilation times

- More complex setup and configuration

- Requires separate compilation and linking

Code comparison

googletest:

#include <gtest/gtest.h>

TEST(MyTest, Addition) {

EXPECT_EQ(2 + 2, 4);

}

ut:

#include <boost/ut.hpp>

int main() {

using namespace boost::ut;

"addition"_test = [] { expect(2 + 2 == 4_i); };

}

Key differences

- ut is header-only, while googletest requires compilation

- ut uses a more modern C++ approach with less boilerplate

- googletest provides more built-in assertions and matchers

- ut offers faster compilation times and simpler integration

- googletest has better IDE integration and debugging support

Both frameworks are suitable for C++ unit testing, but ut focuses on simplicity and performance, while googletest offers a more comprehensive feature set at the cost of increased complexity.

A modern, C++-native, test framework for unit-tests, TDD and BDD - using C++14, C++17 and later (C++11 support is in v2.x branch, and C++03 on the Catch1.x branch)

Pros of Catch2

- More mature and widely adopted in the C++ community

- Extensive documentation and examples available

- Supports a broader range of test types and scenarios

Cons of Catch2

- Slower compilation times, especially for large test suites

- More complex setup and configuration required

- Larger binary size due to its comprehensive feature set

Code Comparison

Catch2:

#define CATCH_CONFIG_MAIN

#include <catch2/catch.hpp>

TEST_CASE("Addition works") {

REQUIRE(1 + 1 == 2);

}

ut:

#include <boost/ut.hpp>

int main() {

using namespace boost::ut;

"Addition works"_test = [] { expect(1 + 1 == 2); };

}

Summary

Catch2 is a more established and feature-rich testing framework, offering comprehensive documentation and support for various testing scenarios. However, it comes with longer compilation times and a more complex setup. ut, on the other hand, provides a lightweight and header-only alternative with faster compilation times and a simpler syntax. The choice between the two depends on project requirements, team familiarity, and performance considerations.

The fastest feature-rich C++11/14/17/20/23 single-header testing framework

Pros of doctest

- Easier to set up and use, with a simpler API

- More mature and stable, with a larger user base

- Better documentation and examples available

Cons of doctest

- Slower compile times compared to ut

- Less feature-rich, lacking some advanced capabilities

Code Comparison

doctest:

#define DOCTEST_CONFIG_IMPLEMENT_WITH_MAIN

#include "doctest.h"

TEST_CASE("basic test") {

CHECK(1 + 1 == 2);

}

ut:

#include <boost/ut.hpp>

int main() {

using namespace boost::ut;

"basic test"_test = [] { expect(1 + 1 == 2_i); };

}

Summary

Both doctest and ut are lightweight C++ testing frameworks. doctest is more established and user-friendly, making it a good choice for beginners or projects that prioritize ease of use. ut, on the other hand, offers faster compile times and more advanced features, which may be beneficial for larger projects or experienced developers who need fine-grained control over their testing environment.

The choice between the two frameworks ultimately depends on the specific needs of the project and the preferences of the development team. Both have their strengths and can be effective tools for unit testing in C++ projects.

A modern formatting library

Pros of fmt

- Widely adopted and battle-tested formatting library

- Extensive documentation and community support

- Supports a wide range of formatting options and types

Cons of fmt

- Larger library size compared to ut

- May have a steeper learning curve for beginners

- Focused solely on formatting, while ut is a testing framework

Code Comparison

fmt example:

#include <fmt/core.h>

int main() {

fmt::print("Hello, {}!", "world");

return 0;

}

ut example:

#include <boost/ut.hpp>

int main() {

using namespace boost::ut;

"hello world"_test = [] {

expect(true);

};

}

Key Differences

- Purpose: fmt is a formatting library, while ut is a unit testing framework

- Scope: fmt focuses on string formatting and output, ut on writing and running tests

- Integration: fmt can be used in various contexts, ut is specifically for C++ testing

- Syntax: fmt uses a printf-like syntax, ut employs a unique DSL for test declarations

- Dependencies: fmt is standalone, ut is part of the Boost ecosystem

Use Cases

- Choose fmt for advanced string formatting and output needs

- Opt for ut when looking for a lightweight, modern C++ testing framework

- Consider using both in a project for their respective strengths

Convert  designs to code with AI

designs to code with AI

Introducing Visual Copilot: A new AI model to turn Figma designs to high quality code using your components.

Try Visual CopilotREADME

"If you liked it then you

"should have put a"_teston it", Beyonce rule

UT / μt

| Motivation | Quick Start | Overview | Tutorial | Examples | User Guide | FAQ | Benchmarks |

C++ single header/single module, macro-free μ(micro)/Unit Testing Framework

#include <boost/ut.hpp> // import boost.ut;

constexpr auto sum(auto... values) { return (values + ...); }

int main() {

using namespace boost::ut;

"sum"_test = [] {

expect(sum(0) == 0_i);

expect(sum(1, 2) == 3_i);

expect(sum(1, 2) > 0_i and 41_i == sum(40, 2));

};

}

Running "sum"...

sum.cpp:11:FAILED [(3 > 0 and 41 == 42)]

FAILED

===============================================================================

tests: 1 | 1 failed

asserts: 3 | 2 passed | 1 failed

Motivation

Testing is a very important part of the Software Development, however, C++ doesn't provide any good testing facilities out of the box, which often leads into a poor testing experience for develops and/or lack of tests/coverage in general.

One should treat testing code as production code!

Additionally, well established testing practises such as Test Driven Development (TDD)/Behaviour Driven Development (BDD) are often not followed due to the same reasons.

The following snippet is a common example of testing with projects in C++.

int main() {

// should sum numbers

{

assert(3 == sum(1, 2));

}

}

There are quite a few problems with the approach above

- No names for tests (Hard to follow intentions by further readers)

- No automatic registration of tests (No way to run specific tests)

- Hard to debug (Assertions don't provide any information why it failed)

- Hard to scale (No easy path forward for parameterized tests, multiple suites, parallel execution, etc...)

- Hard to integrate (No easy way to have a custom output such as XML for CI integration)

- Easy to make mistakes (With implicit casting, floating point comparison, pointer comparison for strings, etc...)

- Hard to follow good practises such as

TDD/BDD(Lack of support for sections and declarative expressions) - ...

UT is trying to address these issues by simplifying testing experience with a few simple steps:

- Just get a single header or module+header

- Integrate it into your project

- Learn a few simple concepts (expect, test, suite)

And you good to go!

Okay, great, but why I would use UT over other/similar testing frameworks already available in C++?

Great question! There are a few unique features which makes UT worth trying

- Firstly, it supports all the basic Unit Testing Framework features (automatic registration of tests, assertions, suites, etc...)

- It's easy to integrate (it's just one header/module)

- It's macro free which makes testing experience that much nicer (it uses modern C++ features instead, macros are opt-in rather than being compulsory - Can I still use macros?)

- It's flexible (all parts of the framework such as: runner, reporter, printer can be customized, basically most other Unit Testing Frameworks can be implemented on top of UT primitives)

- It has smaller learning curve (just a few simple concepts (expect, test, suite))

- It leverages C++ features to support more complex testing (parameterized)

- It's faster to compile and execute than similar frameworks which makes it suitable for bigger projects without additional hassle (Benchmarks)

- It supports TDD/BDD workflows

- It supports Gherkin specification

- It supports Spec

- ...

Sounds intriguing/interesting? Learn more at

Overview

- No dependencies (C++20, Tested Compilers: GCC-9+, Clang-9.0+, Apple Clang-11.0.0+, MSVC-2019+*, Clang-cl-9.0+

- Single header/module (boost/ut.hpp)

- Macro-free (How does it work?)

- Easy to use (Minimal API -

test, suite, operators, literals, [expect]) - Fast to compile/execute (Benchmarks)

- Features (Assertions, Suites, Tests, Sections, Parameterized, BDD, Gherkin, Spec, Matchers, Logging, Runners, Reporters, ...)

- Integrations (ApprovalTests.cpp)

Tutorial

Step 0: Get it...

Get the latest latest header/module from here!

Include/Import

// #include <boost/ut.hpp> // single header

// import boost.ut; // single module (C++20)

int main() { }

Compile & Run

$CXX main.cpp && ./a.out

All tests passed (0 assert in 0 test)

[Optional] Install it

cmake -Bbuild -H.

cd build && make # run tests

cd build && make install # install

[Optional] CMake integration

This project provides a CMake config and target.

Just load ut with find_package to import the Boost::ut target.

Linking against this target will add the necessary include directory for the single header file.

This is demonstrated in the following example.

find_package(ut REQUIRED)

add_library(my_test my_test.cpp)

target_link_libraries(my_test PRIVATE Boost::ut)

[Optional] Conan integration

The boost-ext-ut package is available from Conan Center.

Just include it in your project's Conanfile with boost-ext-ut/2.3.1.

Step 1: Expect it...

Let's write our first assertion, shall we?

int main() {

boost::ut::expect(true);

}

All tests passed (1 asserts in 0 test)

Okay, let's make it fail now?

int main() {

boost::ut::expect(1 == 2);

}

main.cpp:4:FAILED [false]

===============================================================================

tests: 0 | 0 failed

asserts: 1 | 0 passed | 1 failed

Notice that expression

1 == 2hasn't been printed. Instead we gotfalse?

Let's print it then?

int main() {

using namespace boost::ut;

expect(1_i == 2);

}

main.cpp:4:FAILED [1 == 2]

===============================================================================

tests: 0 | 0 failed

asserts: 1 | 0 passed | 1 failed

Okay, now we have it!

1 == 2has been printed as expected. Notice the User Defined Literal (UDL)1_iwas used._iis a compile-time constant integer value

- It allows to override comparison operators ð

- It disallow comparison of different types ð

See the User-guide for more details.

Alternatively, a

tersenotation (no expect required) can be used.

int main() {

using namespace boost::ut::literals;

using namespace boost::ut::operators::terse;

1_i == 2; // terse notation

}

main.cpp:7:FAILED [1 == 2]

===============================================================================

tests: 0 | 0 failed

asserts: 1 | 0 passed | 1 failed

Other expression syntaxes are also available.

expect(1_i == 2); // UDL syntax

expect(1 == 2_i); // UDL syntax

expect(that % 1 == 2); // Matcher syntax

expect(eq(1, 2)); // eq/neq/gt/ge/lt/le

main.cpp:6:FAILED [1 == 2]

main.cpp:7:FAILED [1 == 2]

main.cpp:8:FAILED [1 == 2]

main.cpp:9:FAILED [1 == 2]

===============================================================================

tests: 0 | 0 failed

asserts: 4 | 0 passed | 4 failed

Okay, but what about the case if my assertion is fatal. Meaning that the program will crash unless the processing will be terminated. Nothing easier, let's just add

fatalcall to make the test fail immediately.

expect(fatal(1 == 2_i)); // fatal assertion

expect(1_i == 2); // not executed

main.cpp:6:FAILED [1 == 2]

===============================================================================

tests: 1 | 1 failed

asserts: 2 | 0 passed | 2 failed

But my expression is more complex than just simple comparisons. Not a problem, logic operators are also supported in the

expectð.

expect(42l == 42_l and 1 == 2_i); // compound expression

main.cpp:5:FAILED [(42 == 42 and 1 == 2)]

===============================================================================

tests: 0 | 0 failed

asserts: 1 | 0 passed | 1 failed

Can I add a custom message though? Sure,

expectcalls are streamable!

int main() {

expect(42l == 42_l and 1 == 2_i) << "additional info";

}

main.cpp:5:FAILED [(42 == 42 and 1 == 2)] additional info

===============================================================================

tests: 0 | 0 failed

asserts: 1 | 0 passed | 1 failed

That's nice, can I use custom messages and fatal assertions? Yes, stream the

fatal!

expect(fatal(1 == 2_i)) << "fatal assertion";

expect(1_i == 2);

FAILED

in: main.cpp:6 - test condition: [1 == 2]

fatal assertion

===============================================================================

tests: 0 | 2 failed

asserts: 0 | 0 passed | 2 failed

I use

std::expected, can I stream itserror()upon failure? Yes, sincestd::expected'serror()can only be called when there is no value it requires lazy evaluation.

"lazy log"_test = [] {

std::expected<bool, std::string> e = std::unexpected("lazy evaluated");

expect(e.has_value()) << [&] { return e.error(); } << fatal;

expect(e.value() == true);

};

Running test "lazy log"... FAILED

in: main.cpp:12 - test condition: [false]

lazy evaluated

===============================================================================

tests: 1 | 2 failed

asserts: 0 | 0 passed | 2 failed

Step 2: Group it...

Assertions are great, but how to combine them into more cohesive units?

Test casesare the way to go! They allow to group expectations for the same functionality into coherent units.

"hello world"_test = [] { };

Alternatively

test("hello world") = [] {}can be used.

All tests passed (0 asserts in 1 tests)

Notice

1 testsbut0 asserts.

Let's make our first end-2-end test case, shall we?

int main() {

"hello world"_test = [] {

int i = 43;

expect(42_i == i);

};

}

Running "hello world"...

main.cpp:8:FAILED [42 == 43]

FAILED

===============================================================================

tests: 1 | 1 failed

asserts: 1 | 0 passed | 1 failed

ð We are done here!

I'd like to nest my tests, though and share setup/tear-down. With lambdas used to represents

tests/sectionswe can easily achieve that. Let's just take a look at the following example.

int main() {

"[vector]"_test = [] {

std::vector<int> v(5);

expect(fatal(5_ul == std::size(v)));

should("resize bigger") = [v] { // or "resize bigger"_test

mut(v).resize(10);

expect(10_ul == std::size(v));

};

expect(fatal(5_ul == std::size(v)));

should("resize smaller") = [=]() mutable { // or "resize smaller"_test

v.resize(0);

expect(0_ul == std::size(v));

};

}

}

All tests passed (4 asserts in 1 tests)

Nice! That was easy, but I'm a believer into Behaviour Driven Development (

BDD). Is there a support for that? Yes! Same example as above just with theBDDsyntax.

int main() {

"vector"_test = [] {

given("I have a vector") = [] {

std::vector<int> v(5);

expect(fatal(5_ul == std::size(v)));

when("I resize bigger") = [=] {

mut(v).resize(10);

then("The size should increase") = [=] {

expect(10_ul == std::size(v));

};

};

};

};

}

All tests passed (2 asserts in 1 tests)

On top of that,

feature/scenarioaliases can be leveraged.

int main() {

feature("vector") = [] {

scenario("size") = [] {

given("I have a vector") = [] {

std::vector<int> v(5);

expect(fatal(5_ul == std::size(v)));

when("I resize bigger") = [=] {

mut(v).resize(10);

then("The size should increase") = [=] {

expect(10_ul == std::size(v));

};

};

};

};

};

}

All tests passed (2 asserts in 1 tests)

Can I use

Gherkin? Yeah, let's rewrite the example usingGherkinspecification

int main() {

bdd::gherkin::steps steps = [](auto& steps) {

steps.feature("Vector") = [&] {

steps.scenario("*") = [&] {

steps.given("I have a vector") = [&] {

std::vector<int> v(5);

expect(fatal(5_ul == std::size(v)));

steps.when("I resize bigger") = [&] {

v.resize(10);

};

steps.then("The size should increase") = [&] {

expect(10_ul == std::size(v));

};

};

};

};

};

"Vector"_test = steps |

R"(

Feature: Vector

Scenario: Resize

Given I have a vector

When I resize bigger

Then The size should increase

)";

}

All tests passed (2 asserts in 1 tests)

Nice, is

Specnotation supported as well?

int main() {

describe("vector") = [] {

std::vector<int> v(5);

expect(fatal(5_ul == std::size(v)));

it("should resize bigger") = [v] {

mut(v).resize(10);

expect(10_ul == std::size(v));

};

};

}

All tests passed (2 asserts in 1 tests)

That's great, but how can call the same tests with different arguments/types to be DRY (Don't Repeat Yourself)? Parameterized tests to the rescue!

int main() {

for (auto i : std::vector{1, 2, 3}) {

test("parameterized " + std::to_string(i)) = [i] { // 3 tests

expect(that % i > 0); // 3 asserts

};

}

}

All tests passed (3 asserts in 3 tests)

That's it ð®! Alternatively, a convenient test syntax is also provided ð

int main() {

"args"_test = [](const auto& arg) {

expect(arg > 0_i) << "all values greater than 0";

} | std::vector{1, 2, 3};

}

All tests passed (3 asserts in 3 tests)

Check Examples for further reading.

Step 3: Scale it...

Okay, but my project is more complex than that. How can I scale?

Test suiteswill make that possible. By usingsuitein translation unitstestsdefined inside will be automatically registered ð

suite errors = [] { // or suite<"nameofsuite">

"exception"_test = [] {

expect(throws([] { throw 0; })) << "throws any exception";

};

"failure"_test = [] {

expect(aborts([] { assert(false); }));

};

};

int main() { }

All tests passed (2 asserts in 2 tests)

What's next?

Examples

Assertions

// operators

expect(0_i == sum());

expect(2_i != sum(1, 2));

expect(sum(1) >= 0_i);

expect(sum(1) <= 1_i);

// message

expect(3_i == sum(1, 2)) << "wrong sum";

// expressions

expect(0_i == sum() and 42_i == sum(40, 2));

expect(0_i == sum() or 1_i == sum()) << "compound";

// matchers

expect(that % 0 == sum());

expect(that % 42 == sum(40, 2) and that % (1 + 2) == sum(1, 2));

expect(that % 1 != 2 or 2_i > 3);

// eq/neq/gt/ge/lt/le

expect(eq(42, sum(40, 2)));

expect(neq(1, 2));

expect(eq(sum(1), 1) and neq(sum(1, 2), 2));

expect(eq(1, 1) and that % 1 == 1 and 1_i == 1);

// floating points

expect(42.1_d == 42.101) << "epsilon=0.1";

expect(42.10_d == 42.101) << "epsilon=0.01";

expect(42.10000001 == 42.1_d) << "epsilon=0.1";

// constant

constexpr auto compile_time_v = 42;

auto run_time_v = 99;

expect(constant<42_i == compile_time_v> and run_time_v == 99_i);

// failure

expect(1_i == 2) << "should fail";

expect(sum() == 1_i or 2_i == sum()) << "sum?";

assertions.cpp:53:FAILED [1 == 2] should fail

assertions.cpp:54:FAILED [(0 == 1 or 2 == 0)] sum?

===============================================================================

tests: 0 | 0 failed

asserts: 20 | 18 passed | 2 failed

Tests

Run/Skip/Tag

"run UDL"_test = [] {

expect(42_i == 42);

};

skip / "don't run UDL"_test = [] {

expect(42_i == 43) << "should not fire!";

};

All tests passed (1 asserts in 1 tests)

1 tests skipped

test("run function") = [] {

expect(42_i == 42);

};

skip / test("don't run function") = [] {

expect(42_i == 43) << "should not fire!";

};

All tests passed (1 asserts in 1 tests)

1 tests skipped

tag("nightly") / tag("slow") /

"performance"_test= [] {

expect(42_i == 42);

};

tag("slow") /

"run slowly"_test= [] {

expect(42_i == 43) << "should not fire!";

};

cfg<override> = {.tag = {"nightly"}};

All tests passed (1 asserts in 1 tests)

1 tests skipped

Sections

"[vector]"_test = [] {

std::vector<int> v(5);

expect(fatal(5_ul == std::size(v)));

should("resize bigger") = [=] { // or "resize bigger"_test

mut(v).resize(10);

expect(10_ul == std::size(v));

};

expect(fatal(5_ul == std::size(v)));

should("resize smaller") = [=]() mutable { // or "resize smaller"_test

v.resize(0);

expect(0_ul == std::size(v));

};

};

All tests passed (4 asserts in 1 tests)

Behavior Driven Development (BDD)

"Scenario"_test = [] {

given("I have...") = [] {

when("I run...") = [] {

then("I expect...") = [] { expect(1_i == 1); };

then("I expect...") = [] { expect(1 == 1_i); };

};

};

};

All tests passed (2 asserts in 1 tests)

Gherkin

int main() {

bdd::gherkin::steps steps = [](auto& steps) {

steps.feature("*") = [&] {

steps.scenario("*") = [&] {

steps.given("I have a number {value}") = [&](int value) {

auto number = value;

steps.when("I add {value} to it") = [&](int value) {

number += value;

};

steps.then("I expect number to be {value}") = [&](int value) {

expect(that % number == value);

};

};

};

};

};

"Gherkin"_test = steps |

R"(

Feature: Number

Scenario: Addition

Given I have a number 40

When I add 2 to it

Then I expect number to be 42

)";

}

All tests passed (1 asserts in 1 tests)

Spec

int main() {

describe("equality") = [] {

it("should be equal") = [] { expect(0_i == 0); };

it("should not be equal") = [] { expect(1_i != 0); };

};

}

All tests passed (2 asserts in 1 tests)

Parameterized

for (auto i : std::vector{1, 2, 3}) {

test("parameterized " + std::to_string(i)) = [i] {

expect(that % i > 0);

};

}

"args"_test =

[](auto arg) {

expect(arg >= 1_i);

}

| std::vector{1, 2, 3};

"types"_test =

[]<class T> {

expect(std::is_integral_v<T>) << "all types are integrals";

}

| std::tuple<bool, int>{};

"args and types"_test =

[]<class TArg>(TArg arg) {

expect(fatal(std::is_integral_v<TArg>));

expect(42_i == arg or "is true"_b == arg);

expect(type<TArg> == type<int> or type<TArg> == type<bool>);

}

| std::tuple{true, 42};

When using the operator| syntax instead of a for loop, the test name will automatically

be extended to avoid duplicate names. For example, the test name for the args and types test

will be args and types (true, bool) for the first parameter and args and types (42, int)

for the second parameter. For simple built-in types (integral types and floating point numbers),

the test name will contain the parameter values. For other types, the parameters will simply be

enumerated. For example, if we would extend the test above to use

std::tuple{true, 42, std::complex<double>{0.5, 1}}, the test name in the third run would be

args and types (3rd parameter, std::complex<double>). If you want to have the actual value of

a non-integral type included in the test name, you can overload the format_test_parameter function.

See the example on parameterized tests

for details.

All tests passed (14 asserts in 10 tests)

And whenever I need to know the specific type for which the test failed, I can use

reflection::type_name<T>(), like this:

"types with type name"_test =

[]<class T>() {

expect(std::is_unsigned_v<T>) << reflection::type_name<T>() << "is unsigned";

}

| std::tuple<unsigned int, float>{};

Running "types with type name"...PASSED

Running "types with type name"...

<source>:10:FAILED [false] float is unsigned

FAILED

Suites

namespace ut = boost::ut;

ut::suite errors = [] {

using namespace ut;

"throws"_test = [] {

expect(throws([] { throw 0; }));

};

"doesn't throw"_test = [] {

expect(nothrow([]{}));

};

};

int main() { }

All tests passed (2 asserts in 2 tests)

Misc

Logging using streams

"logging"_test = [] {

log << "pre";

expect(42_i == 43) << "message on failure";

log << "post";

};

Running "logging"...

pre

logging.cpp:8:FAILED [42 == 43] message on failure

post

FAILED

===============================================================================

tests: 1 | 1 failed

asserts: 1 | 0 passed | 1 failed

Logging using formatting

This requires using C++20 with a standard library with std::format support.

"logging"_test = [] {

log("\npre {} == {}\n", 42, 43);

expect(42_i == 43) << "message on failure";

log("\npost {} == {} -> {}\n", 42, 43, 42 == 43);

};

Running "logging"...

pre 42 == 43

logging.cpp:8:FAILED [42 == 43] message on failure

post 42 == 43 -> false

FAILED

===============================================================================

tests: 1 | 1 failed

asserts: 1 | 0 passed | 1 failed

Matchers

"matchers"_test = [] {

constexpr auto is_between = [](auto lhs, auto rhs) {

return [=](auto value) {

return that % value >= lhs and that % value <= rhs;

};

};

expect(is_between(1, 100)(42));

expect(not is_between(1, 100)(0));

};

All tests passed (2 asserts in 1 tests)

Exceptions/Aborts

"exceptions/aborts"_test = [] {

expect(throws<std::runtime_error>([] { throw std::runtime_error{""}; }))

<< "throws runtime_error";

expect(throws([] { throw 0; })) << "throws any exception";

expect(nothrow([]{})) << "doesn't throw";

expect(aborts([] { assert(false); }));

};

All tests passed (4 asserts in 1 tests)

Config

Runner

namespace ut = boost::ut;

namespace cfg {

class runner {

public:

template <class... Ts> auto on(ut::events::test<Ts...> test) { test(); }

template <class... Ts> auto on(ut::events::skip<Ts...>) {}

template <class TExpr>

auto on(ut::events::assertion<TExpr>) -> bool { return true; }

auto on(ut::events::fatal_assertion) {}

template <class TMsg> auto on(ut::events::log<TMsg>) {}

};

} // namespace cfg

template<> auto ut::cfg<ut::override> = cfg::runner{};

Reporter

namespace ut = boost::ut;

namespace cfg {

class reporter {

public:

auto on(ut::events::test_begin) -> void {}

auto on(ut::events::test_run) -> void {}

auto on(ut::events::test_skip) -> void {}

auto on(ut::events::test_end) -> void {}

template <class TMsg> auto on(ut::events::log<TMsg>) -> void {}

template <class TExpr>

auto on(ut::events::assertion_pass<TExpr>) -> void {}

template <class TExpr>

auto on(ut::events::assertion_fail<TExpr>) -> void {}

auto on(ut::events::fatal_assertion) -> void {}

auto on(ut::events::exception) -> void {}

auto on(ut::events::summary) -> void {}

};

} // namespace cfg

template <>

auto ut::cfg<ut::override> = ut::runner<cfg::reporter>{};

Printer

namespace ut = boost::ut;

namespace cfg {

struct printer : ut::printer {

template <class T>

auto& operator<<(T&& t) {

std::cerr << std::forward<T>(t);

return *this;

}

};

} // namespace cfg

template <>

auto ut::cfg<ut::override> = ut::runner<ut::reporter<cfg::printer>>{};

int main() {

using namespace ut;

"printer"_test = [] {};

}

User Guide

API

export module boost.ut; /// __cpp_modules

namespace boost::inline ext::ut::inline v2_3_1 {

/**

* Represents test suite object

*/

struct suite final {

/**

* Creates and executes test suite

* @example suite _ = [] {};

* @param suite test suite function

*/

constexpr explicit(false) suite(auto suite);

};

/**

* Creates a test

* @example "name"_test = [] {};

* @return test object to be executed

*/

constexpr auto operator""_test;

/**

* Creates a test

* @example test("name") = [] {};

* @return test object to be executed

*/

constexpr auto test = [](const auto name);

/**

* Creates a test

* @example should("name") = [] {};

* @return test object to be executed

*/

constexpr auto should = [](const auto name);

/**

* Behaviour Driven Development (BDD) helper functions

* @param name step name

* @return test object to be executed

*/

constexpr auto given = [](const auto name);

constexpr auto when = [](const auto name);

constexpr auto then = [](const auto name);

/**

* Evaluates an expression

* @example expect(42 == 42_i and 1 != 2_i);

* @param expr expression to be evaluated

* @param source location https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/utility/source_location

* @return stream

*/

constexpr OStream& expect(

Expression expr,

const std::source_location& location = std::source_location::current()

);

struct {

/**

* @example (that % 42 == 42);

* @param expr expression to be evaluated

*/

[[nodiscard]] constexpr auto operator%(Expression expr) const;

} that{};

inline namespace literals {

/**

* User defined literals to represent constant values

* @example 42_i, 0_uc, 1.23_d

*/

constexpr auto operator""_i; /// int

constexpr auto operator""_s; /// short

constexpr auto operator""_c; /// char

constexpr auto operator""_l; /// long

constexpr auto operator""_ll; /// long long

constexpr auto operator""_u; /// unsigned

constexpr auto operator""_uc; /// unsigned char

constexpr auto operator""_us; /// unsigned short

constexpr auto operator""_ul; /// unsigned long

constexpr auto operator""_f; /// float

constexpr auto operator""_d; /// double

constexpr auto operator""_ld; /// long double

/**

* Represents dynamic values

* @example _i(42), _f(42.)

*/

constexpr auto _b(bool);

constexpr auto _c(char);

constexpr auto _s(short);

constexpr auto _i(int);

constexpr auto _l(long);

constexpr auto _ll(long long);

constexpr auto _u(unsigned);

constexpr auto _uc(unsigned char);

constexpr auto _us(unsigned short);

constexpr auto _ul(unsigned long);

constexpr auto _f(float);

constexpr auto _d(double);

constexpr auto _ld(long double);

/**

* Logical representation of constant boolean (true) value

* @example "is set"_b : true

* not "is set"_b : false

*/

constexpr auto operator ""_b;

} // namespace literals

inline namespace operators {

/**

* Comparison functions to be used in expressions

* @example eq(42, 42), neq(1, 2)

*/

constexpr auto eq(Operator lhs, Operator rhs); /// ==

constexpr auto neq(Operator lhs, Operator rhs); /// !=

constexpr auto gt(Operator lhs, Operator rhs); /// >

constexpr auto ge(Operator lhs, Operator rhs); /// >=

constexpr auto lt(Operator lhs, Operator rhs); /// <

constexpr auto le(Operator lhs, Operator rhs); /// <=

/**

* Overloaded comparison operators to be used in expressions

* @example (42_i != 0)

*/

constexpr auto operator==;

constexpr auto operator!=;

constexpr auto operator>;

constexpr auto operator>=;

constexpr auto operator<;

constexpr auto operator<=;

/**

* Overloaded logic operators to be used in expressions

* @example (42_i != 0 and 1 == 2_i)

*/

constexpr auto operator and;

constexpr auto operator or;

constexpr auto operator not;

/**

* Executes parameterized tests

* @example "parameterized"_test = [](auto arg) {} | std::tuple{1, 2, 3};

*/

constexpr auto operator|;

/**

* Creates tags

* @example tag("slow") / tag("nightly") / "perf"_test = []{};

*/

constexpr auto operator/;

/**

* Creates a `fatal_assertion` from an expression

* @example (42_i == 0) >> fatal

*/

constexpr auto operator>>;

} // namespace operators

/**

* Creates skippable test object

* @example skip / "don't run"_test = [] { };

*/

constexpr auto skip = tag("skip");

struct {

/**

* @example log << "message!";

* @param msg stringable message

*/

auto& operator<<(Msg msg);

} log{};

/**

* Makes object mutable

* @example mut(object)

* @param t object to be mutated

*/

template<class T> auto mut(const T& t) -> T&;

/**

* Default execution flow policy

*/

class runner {

public:

/**

* @example cfg<override> = {

.filter = "test.section.*",

.colors = { .none = "" },

.dry__run = true

};

* @param options.filter {default: "*"} runs all tests which names

matches test.section.* filter

* @param options.colors {default: {

.none = "\033[0m",

.pass = "\033[32m",

.fail = "\033[31m"

} if specified then overrides default color values

* @param options.dry_run {default: false} if true then print test names to be

executed without running them

*/

auto operator=(options);

/**

* @example suite _ = [] {};

* @param suite() executes suite

*/

template<class TSuite>

auto on(ut::events::suite<TSuite>);

/**

* @example "name"_test = [] {};

* @param test.type ["test", "given", "when", "then"]

* @param test.name "name"

* @param test.arg parameterized argument

* @param test() executes test

*/

template<class... Ts>

auto on(ut::events::test<Ts...>);

/**

* @example skip / "don't run"_test = []{};

* @param skip.type ["test", "given", "when", "then"]

* @param skip.name "don't run"

* @param skip.arg parameterized argument

*/

template<class... Ts>

auto on(ut::events::skip<Ts...>);

/**

* @example file.cpp:42: expect(42_i == 42);

* @param assertion.expr 42_i == 42

* @param assertion.location { "file.cpp", 42 }

* @return true if expr passes, false otherwise

*/

template <class TExpr>

auto on(ut::events::assertion<TExpr>) -> bool;

/**

* @example expect((2_i == 1) >> fatal)

* @note triggered by `fatal`

* should std::exit

*/

auto on(ut::events::fatal_assertion);

/**

* @example log << "message"

* @param log.msg "message"

*/

template<class TMsg>

auto on(ut::events::log<TMsg>);

/**

* Explicitly runs registered test suites

* If not called directly test suites are executed with run's destructor

* @example return run({.report_errors = true})

* @param run_cfg.report_errors {default: false} if true it prints the summary after running

*/

auto run(run_cfg);

/**

* Runs registered test suites if they haven't been explicitly executed already

*/

~run();

};

/**

* Default reporter policy

*/

class reporter {

public:

/**

* @example file.cpp:42: "name"_test = [] {};

* @param test_begin.type ["test", "given", "when", "then"]

* @param test_begin.name "name"

* @param test_begin.location { "file.cpp", 42 }

*/

auto on(ut::events::test_begin) -> void;

/**

* @example "name"_test = [] {};

* @param test_run.type ["test", "given", "when", "then"]

* @param test_run.name "name"

*/

auto on(ut::events::test_run) -> void;

/**

* @example "name"_test = [] {};

* @param test_skip.type ["test", "given", "when", "then"]

* @param test_skip.name "name"

*/

auto on(ut::events::test_skip) -> void;

/**

* @example "name"_test = [] {};

* @param test_end.type ["test", "given", "when", "then"]

* @param test_end.name "name"

*/

auto on(ut::events::test_end) -> void;

/**

* @example log << "message"

* @param log.msg "message"

*/

template<class TMsg>

auto on(ut::events::log<TMsg>) -> void;

/**

* @example file.cpp:42: expect(42_i == 42);

* @param assertion_pass.expr 42_i == 42

* @param assertion_pass.location { "file.cpp", 42 }

*/

template <class TExpr>

auto on(ut::events::assertion_pass<TExpr>) -> void;

/**

* @example file.cpp:42: expect(42_i != 42);

* @param assertion_fail.expr 42_i != 42

* @param assertion_fail.location { "file.cpp", 42 }

*/

template <class TExpr>

auto on(ut::events::assertion_fail<TExpr>) -> void;

/**

* @example expect((2_i == 1) >> fatal)

* @note triggered by `fatal`

* should std::exit

*/

auto on(ut::events::fatal_assertion) -> void;

/**

* @example "exception"_test = [] { throw std::runtime_error{""}; };

*/

auto on(ut::events::exception) -> void;

/**

* @note triggered on destruction of runner

*/

auto on(ut::events::summary) -> void;

};

/**

* Used to override default running policy

* @example template <> auto cfg<override> = runner<reporter>{};

*/

struct override {};

/**

* Default UT execution policy

* Can be overwritten with override

*/

template <class = override> auto cfg = runner<reporter>{};

}

Configuration

| Option | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

BOOST_UT_VERSION | Current version | 2'3'1 |

FAQ

How does it work?

suite

/**

* Represents suite object

* @example suite _ = []{};

*/

struct suite final {

/**

* Assigns and executes test suite

*/

[[nodiscard]] constexpr explicit(false) suite(Suite suite) {

suite();

}

};

test

/**

* Creates named test object

* @example "hello world"_test

* @return test object

*/

[[nodiscard]] constexpr Test operator ""_test(const char* name, std::size_t size) {

return test{{name, size}};

}

/**

* Represents test object

*/

struct test final {

std::string_view name{}; /// test case name

/**

* Assigns and executes test function

* @param test function

*/

constexpr auto operator=(const Test& test) {

std::cout << "Running... " << name << '\n';

test();

}

};

expect

/**

* Evaluates an expression

* @example expect(42_i == 42);

* @param expr expression to be evaluated

* @param source location https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/utility/source_location

* @return stream

*/

constexpr OStream& expect(

Expression expr,

const std::source_location& location = std::source_location::current()

) {

if (not static_cast<bool>(expr) {

std::cerr << location.file()

<< ':'

<< location.line()

<< ":FAILED: "

<< expr

<< '\n';

}

return std::cerr;

}

/**

* Creates constant object for which operators can be overloaded

* @example 42_i

* @return integral constant object

*/

template <char... Cs>

[[nodiscard]] constexpr Operator operator""_i() -> integral_constant<int, value<Cs...>>;

/**

* Overloads comparison if at least one of {lhs, rhs} is an Operator

* @example (42_i == 42)

* @param lhs Left-hand side operator

* @param rhs Right-hand side operator

* @return Comparison object

*/

[[nodiscard]] constexpr auto operator==(Operator lhs, Operator rhs) {

return eq{lhs, rhs};

}

/**

* Comparison Operator

*/

template <Operator TLhs, Operator TRhs>

struct eq final {

TLhs lhs{}; // Left-hand side operator

TRhs rhs{}; // Right-hand side operator

/**

* Performs comparison operation

* @return true if expression is successful

*/

[[nodiscard]] constexpr explicit operator bool() const {

return lhs == rhs;

}

/**

* Nicely prints the operation

*/

friend auto operator<<(OStream& os, const eq& op) -> Ostream& {

return (os << op.lhs << " == " << op.rhs);

}

};

Sections

/**

* Convenient aliases for creating test named object

* @example should("return true") = [] {};

*/

constexpr auto should = [](const auto name) { return test{name}; };

Behaviour Driven Development (BDD)

/**

* Convenient aliases for creating BDD tests

* @example feature("Feature") = [] {};

* @example scenario("Scenario") = [] {};

* @example given("I have an object") = [] {};

* @example when("I call it") = [] {};

* @example then("I should get") = [] {};

*/

constexpr auto feature = [](const auto name) { return test{name}; };

constexpr auto scenario = [](const auto name) { return test{name}; };

constexpr auto given = [](const auto name) { return test{name}; };

constexpr auto when = [](const auto name) { return test{name}; };

constexpr auto then = [](const auto name) { return test{name}; };

Spec

/**

* Convenient aliases for creating Spec tests

* @example describe("test") = [] {};

* @example it("should...") = [] {};

*/

constexpr auto describe = [](const auto name) { return test{name}; };

constexpr auto it = [](const auto name) { return test{name}; };

Try it online

- Header - https://godbolt.org/z/x96n8b

- Module - https://wandbox.org/permlink/LrV7WwIgghTP1nrs

Fast compilation times (Benchmarks)?

Implementation

-

Leveraging C++20 features

-

Avoiding unique types for lambda expressions

template <class Test>

requires not std::convertible_to<Test, void (*)()>>

constexpr auto operator=(Test test);

vs

// Compiles 5x faster because it doesn't introduce a new type for each lambda

constexpr auto operator=(void (*test)());

Type-nameerasure (allows types/function memoization)

eq<integral_constant<42>, int>{ {}, 42 }

vs

// Can be memoized - faster to compile

eq<int, int>{42, 42}

-

Limiting preprocessor work

- Single header/module

- Minimal number of include files

-

Simplified versions of

std::functionstd::string_view

C++20 features?

-

API

-

- Assertions -

expect(false)-__FILE__:__LINE__:FAILED [false]

- Assertions -

-

- Configuration -

cfg<override> = {.filter = "test"}

- Configuration -

-

- Constant matchers -

constant<42_i == 42>

- Constant matchers -

-

Template Parameter List for generic lambdas

- Parameterized tests -

"types"_test = []<class T>() {};

- Parameterized tests -

-

- Operators -

Operator @ Operator

- Operators -

-

import boost.ut;

-

C++2X integration?

Parameterized tests with Expansion statements (https://wg21.link/P1306r1)

template for (auto arg : std::tuple<int, double>{}) {

test("types " + std::to_string(arg)) = [arg] {

expect(type(arg) == type<int> or type(arg) == type<double>);

};

}

All tests passed (2 asserts in 2 tests)

Is standardization an option?

Personally, I believe that C++ standard could benefit from common testing primitives (

expect,""_test) because

- It lowers the entry-level to the language (no need for third-party libraries)

- It improves the education aspect (one standard way of doing it)

- It makes the language more coherent/stable (consistent design with other features, stable API)

- It makes the testing a first class citizen (shows that the community cares about this aspect of the language)

- It allows to publish tests for the Standard Library (STL) in the standard way (coherency, easier to extend)

- It allows to act as additional documentation as a way to verify whether a particular implementation is conforming (quality, self-verification)

- It helps with establishing standard vocabulary for testing (common across STL and other projects)

Can I still use macros?

Sure, although please notice that there are negatives of using macros such as

- Error messages might be not clear and/or point to the wrong line

- Global scope will be polluted

- Type safety will be ignored

#define EXPECT(...) ::boost::ut::expect(::boost::ut::that % __VA_ARGS__)

#define SUITE ::boost::ut::suite _ = []

#define TEST(name) ::boost::ut::detail::test{"test", name} = [=]() mutable

SUITE {

TEST("suite") {

EXPECT(42 == 42);

};

};

int main() {

TEST("macro") {

EXPECT(1 != 2);

};

TEST("vector") {

std::vector<int> v(5);

EXPECT(fatal(5u == std::size(v))) << "fatal";

TEST("resize bigger") {

v.resize(10);

EXPECT(10u == std::size(v));

};

};

}

All tests passed (4 asserts in 3 tests)

What about Mocks/Stubs/Fakes?

Consider using one of the following frameworks

What about Microbenchmarking?

Consider using one of the following frameworks

Related materials/talks?

- [Boost].UT - Unit Testing Framework - Kris Jusiak

- Future of Testing with C++20 - Kris Jusiak

- Macro-Free Testing with C++20 - Kris Jusiak

- "If you liked it then you

"should have put a"_teston it", Beyonce rule - Kris Jusiak - Principles of Unit Testing With C++ - Dave Steffen and Kris Jusiak

- Empirical Unit Testing - Dave Steffen

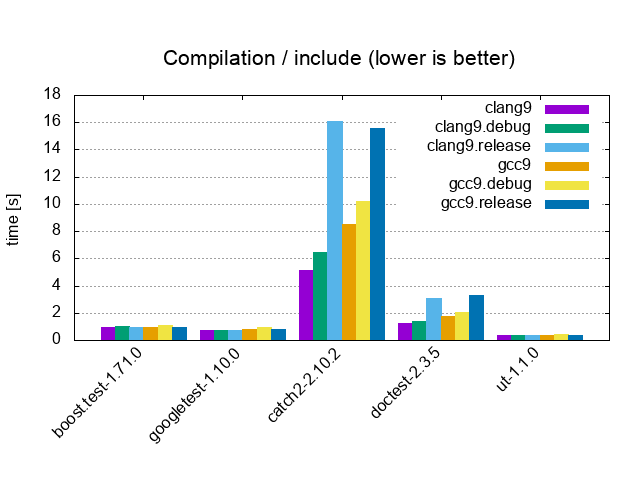

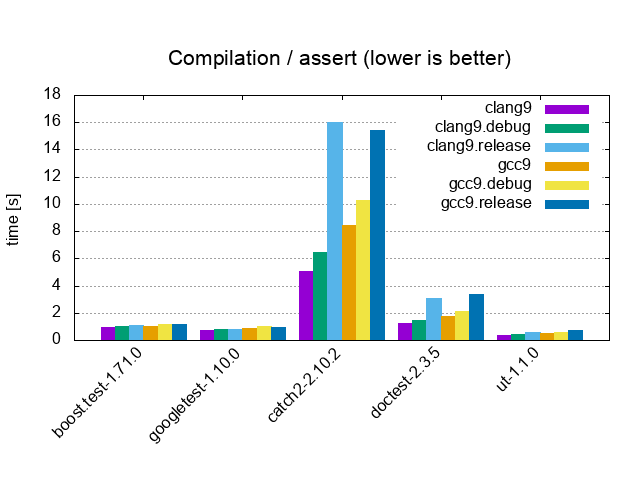

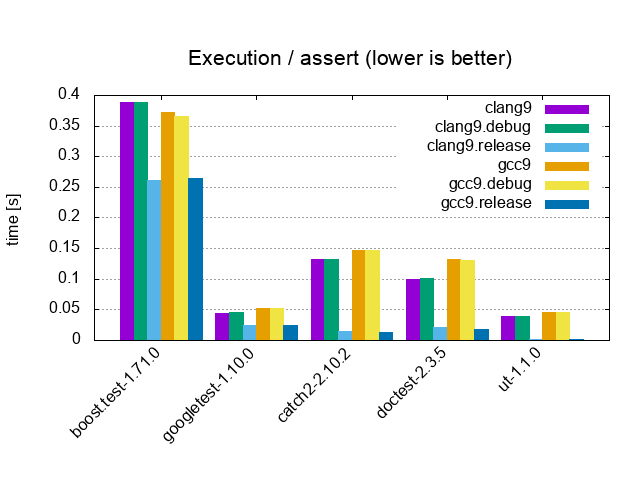

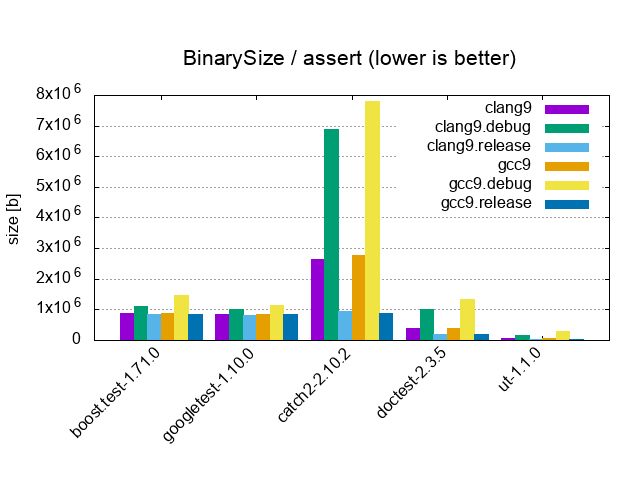

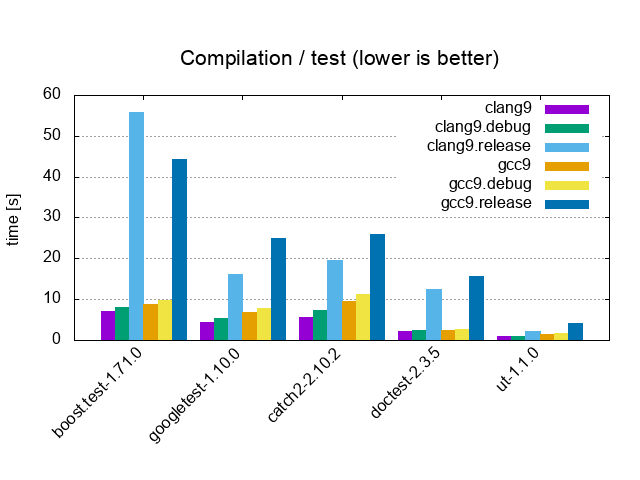

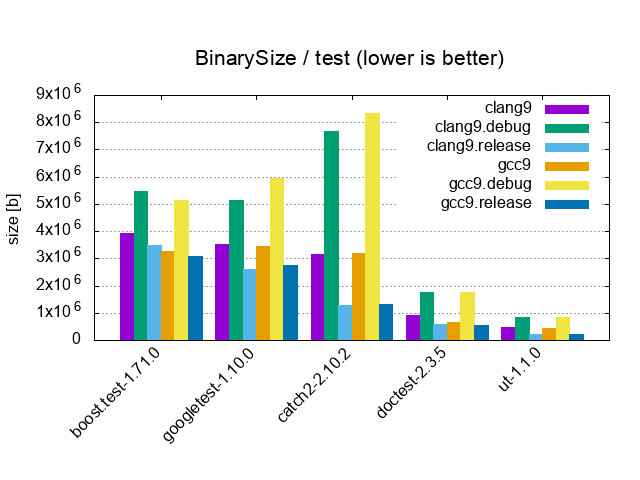

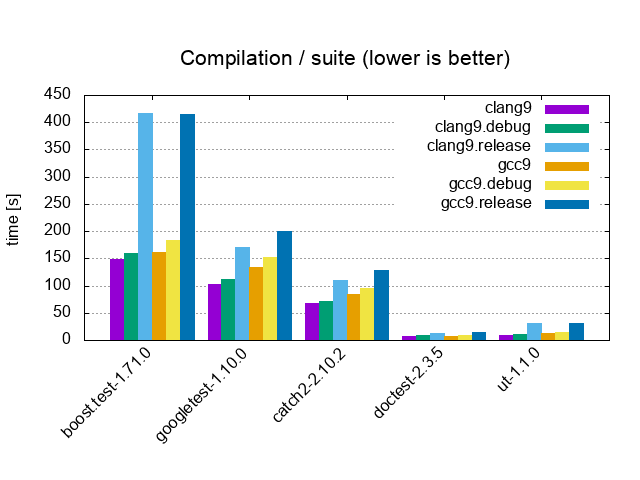

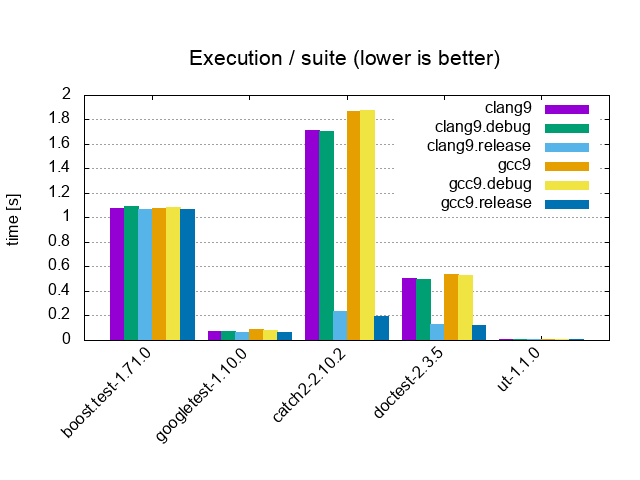

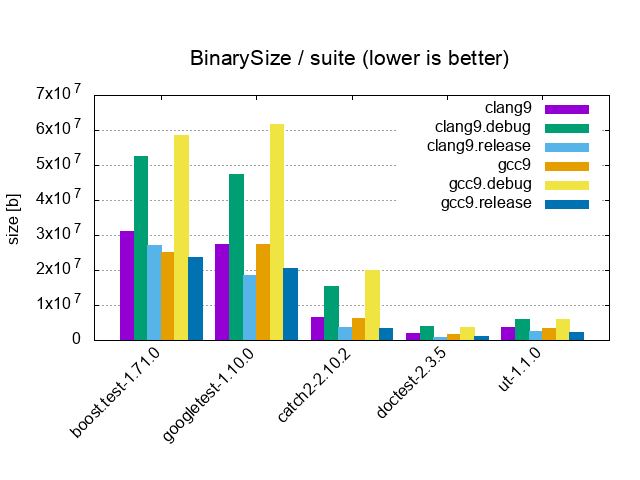

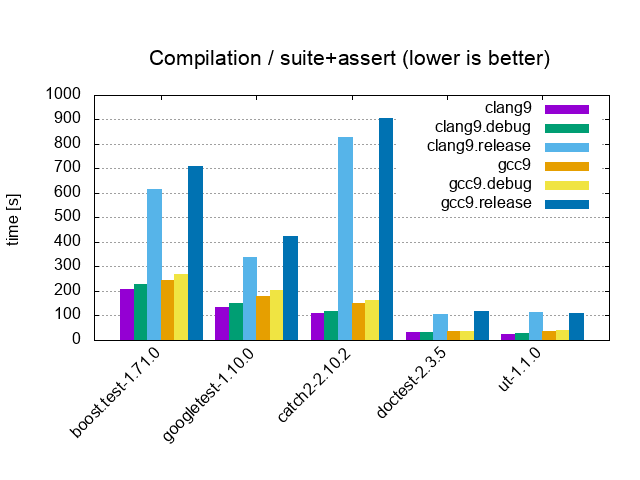

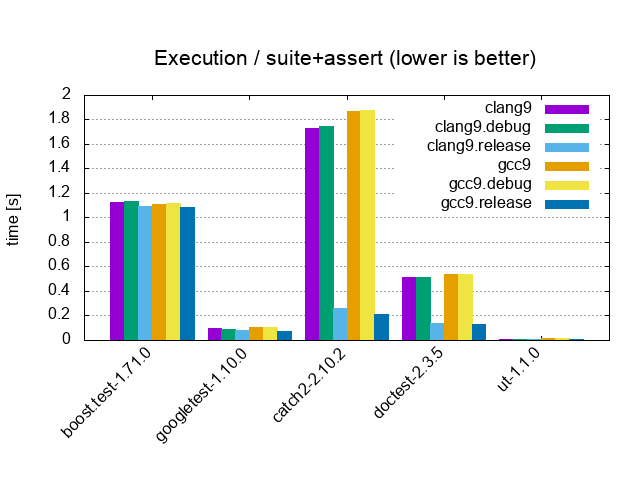

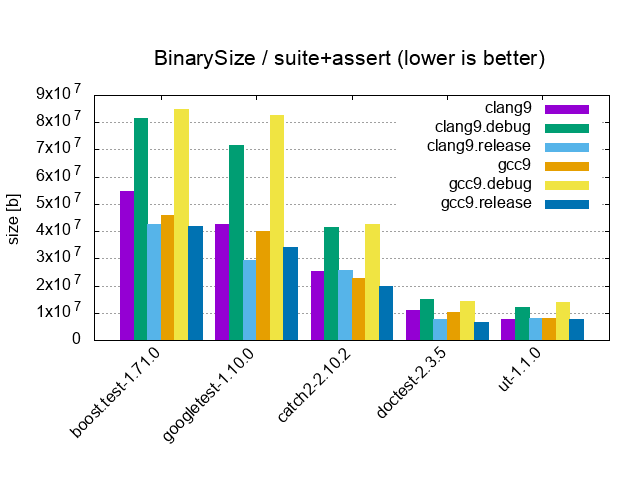

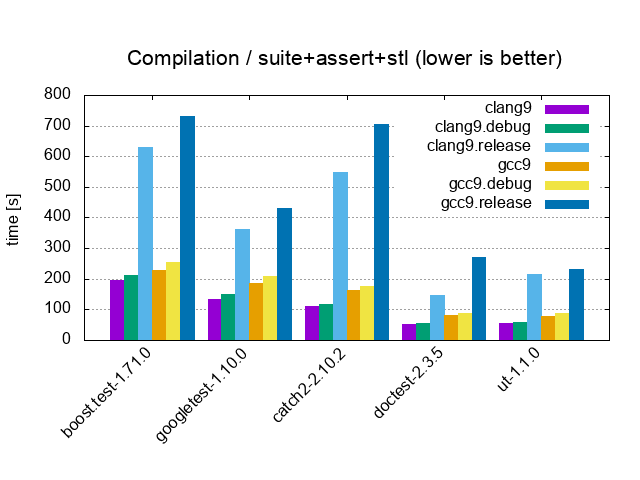

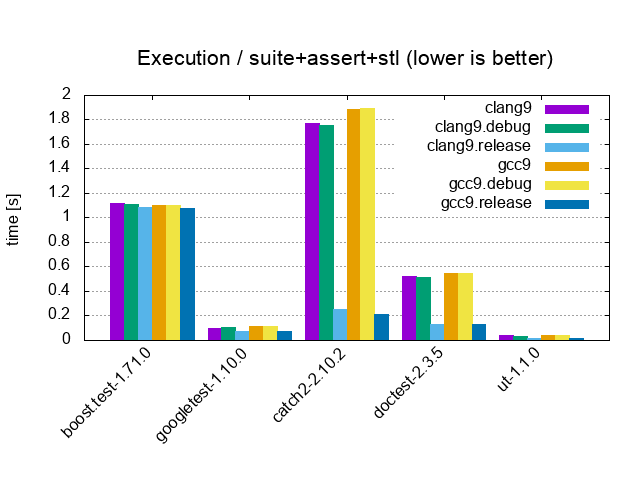

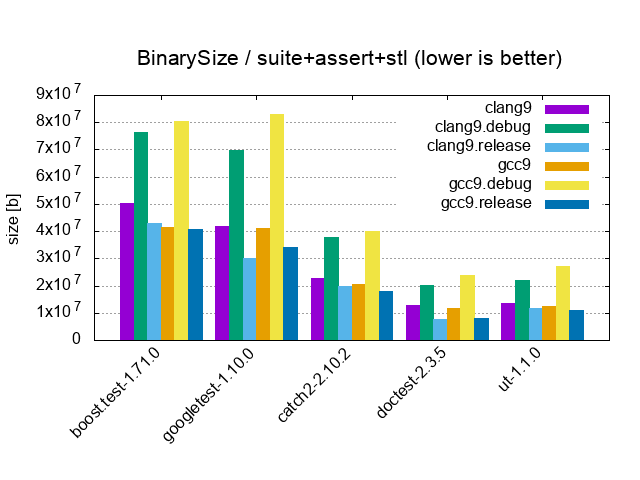

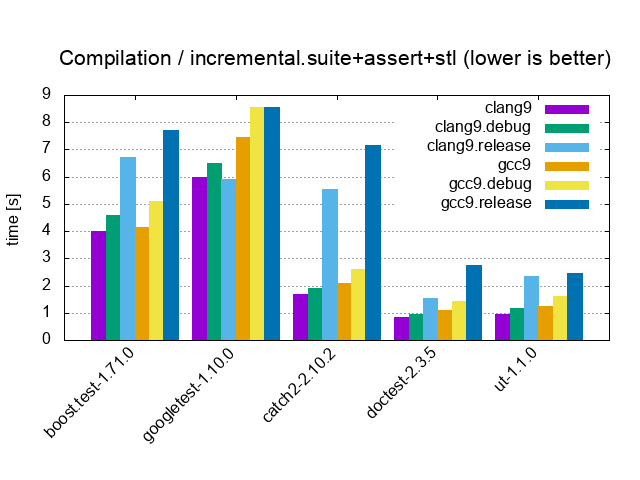

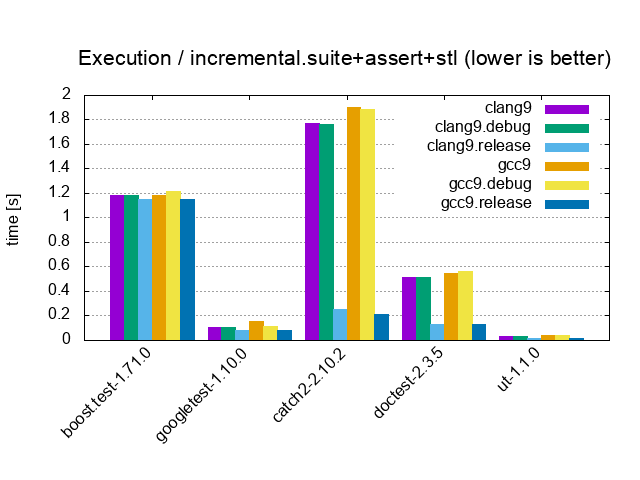

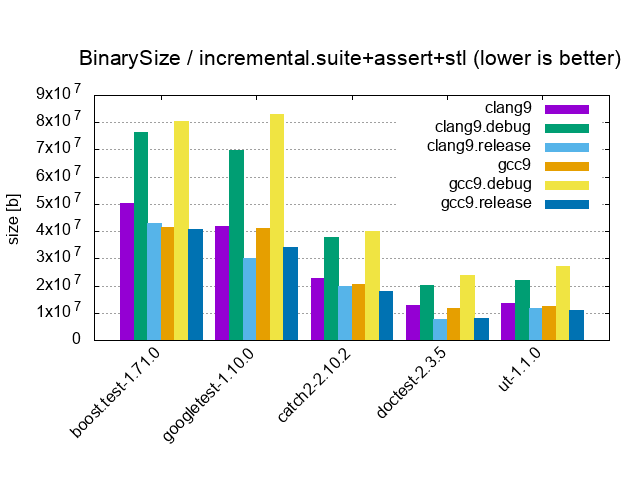

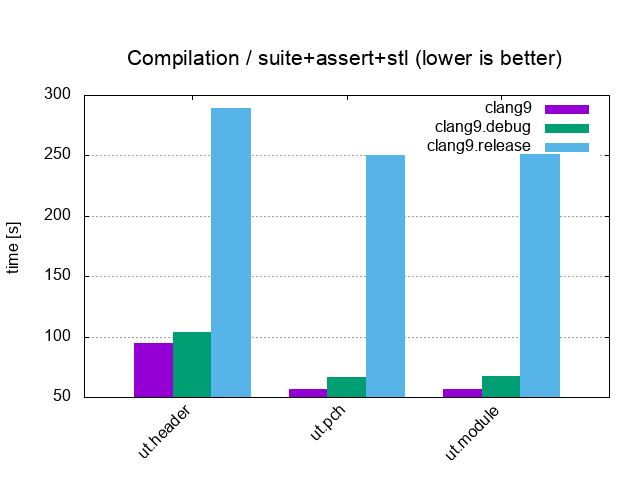

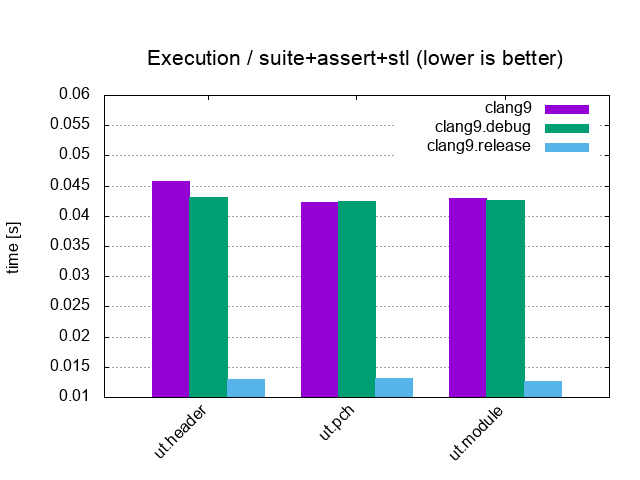

Benchmarks

| Framework | Version | Standard | License | Linkage | Test configuration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boost.Test | 1.71.0 | C++03 | Boost 1.0 | single header/library | static library |

| GoogleTest | 1.10.0 | C++11 | BSD-3 | library | static library |

| Catch | 2.10.2 | C++11 | Boost 1.0 | single header | CATCH_CONFIG_FAST_COMPILE |

| Doctest | 2.3.5 | C++11 | MIT | single header | DOCTEST_CONFIG_SUPER_FAST_ASSERTS |

| UT | 1.1.0 | C++20 | Boost 1.0 | single header/module |

| Include / 0 tests, 0 asserts, 1 cpp file | |||

|

|||

| Assert / 1 test, 1'000'000 asserts, 1 cpp file | |||

|

|

|

|

| Test / 1'000 tests, 0 asserts, 1 cpp file | |||

|

|

|

|

| Suite / 10'000 tests, 0 asserts, 100 cpp files | |||

|

|

|

|

| Suite+Assert / 10'000 tests, 40'000 asserts, 100 cpp files | |||

|

|

|

|

| Suite+Assert+STL / 10'000 tests, 20'000 asserts, 100 cpp files | |||

|

|

|

|

| Incremental Build - Suite+Assert+STL / 1 cpp file change (1'000 tests, 20'000 asserts, 100 cpp files) | |||

|

|

|

|

|

Suite+Assert+STL / 10'000 tests, 20'000 asserts, 100 cpp files (Headers vs Precompiled headers vs C++20 Modules) |

|||

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer UT is not an official Boost library.

Top Related Projects

A modern, C++-native, test framework for unit-tests, TDD and BDD - using C++14, C++17 and later (C++11 support is in v2.x branch, and C++03 on the Catch1.x branch)

GoogleTest - Google Testing and Mocking Framework

A modern, C++-native, test framework for unit-tests, TDD and BDD - using C++14, C++17 and later (C++11 support is in v2.x branch, and C++03 on the Catch1.x branch)

The fastest feature-rich C++11/14/17/20/23 single-header testing framework

A modern formatting library

Convert  designs to code with AI

designs to code with AI

Introducing Visual Copilot: A new AI model to turn Figma designs to high quality code using your components.

Try Visual Copilot