Top Related Projects

A starter template for TypeScript and React with a detailed README describing how to use the two together.

The complete guide to static typing in "React & Redux" apps using TypeScript

Cheatsheets for experienced React developers getting started with TypeScript

The repository for high quality TypeScript type definitions.

:sparkles: Monorepo for all the tooling which enables ESLint to support TypeScript

Quick Overview

The typescript-cheatsheets/react repository is a comprehensive collection of TypeScript best practices and patterns for React development. It serves as a community-driven resource to help developers write type-safe React applications using TypeScript, offering explanations, examples, and tips for common scenarios.

Pros

- Extensive coverage of TypeScript and React integration topics

- Regularly updated with community contributions

- Well-organized and easy to navigate

- Includes both beginner-friendly and advanced content

Cons

- May be overwhelming for complete beginners

- Some sections might become outdated as React and TypeScript evolve

- Lacks interactive examples or playground environment

- Primarily focused on React, limiting its usefulness for other frameworks

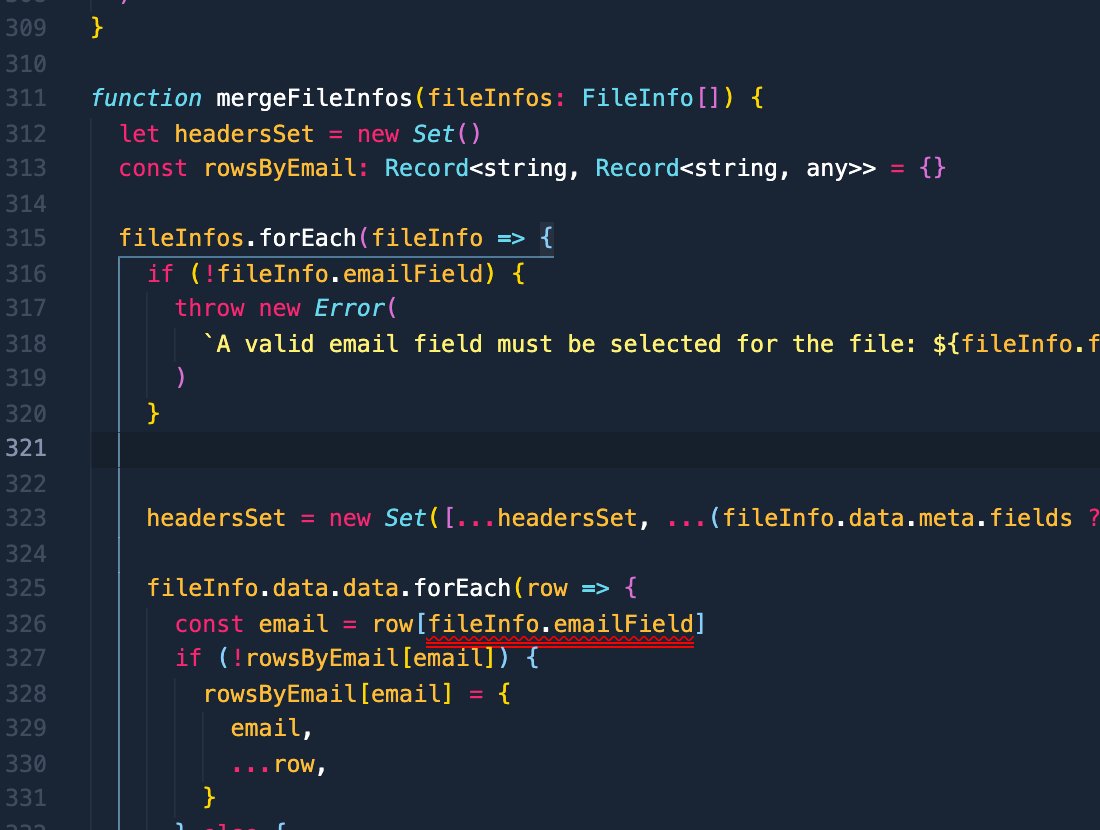

Code Examples

- Basic functional component with props:

type GreetingProps = {

name: string;

};

const Greeting: React.FC<GreetingProps> = ({ name }) => {

return <h1>Hello, {name}!</h1>;

};

- Using useState hook with TypeScript:

const [count, setCount] = useState<number>(0);

const increment = () => setCount(prevCount => prevCount + 1);

- Typing event handlers:

const handleChange = (event: React.ChangeEvent<HTMLInputElement>) => {

console.log(event.target.value);

};

<input onChange={handleChange} />;

- Using generics with custom hooks:

function useLocalStorage<T>(key: string, initialValue: T): [T, (value: T) => void] {

// Implementation details omitted for brevity

}

const [name, setName] = useLocalStorage<string>("name", "");

Getting Started

To get started with the typescript-cheatsheets/react resource:

- Visit the GitHub repository: https://github.com/typescript-cheatsheets/react

- Browse the table of contents in the README.md file

- Click on specific sections to dive deeper into topics

- For a quick start, check out the "Basic Cheatsheet (A-Z)" section

- Explore advanced topics in the "Advanced Cheatsheet" section

- Contribute by opening issues or submitting pull requests for improvements or corrections

Competitor Comparisons

A starter template for TypeScript and React with a detailed README describing how to use the two together.

Pros of TypeScript-React-Starter

- Provides a complete project setup with Create React App

- Includes example components and tests

- Offers a more structured starting point for beginners

Cons of TypeScript-React-Starter

- Less frequently updated compared to react

- Focuses on a specific project structure, which may not suit all needs

- Limited in-depth TypeScript explanations

Code Comparison

TypeScript-React-Starter:

import * as React from 'react';

import './App.css';

import Hello from './components/Hello';

function App() {

return (

<div className="App">

<Hello name="TypeScript" enthusiasmLevel={10} />

</div>

);

}

react:

type Props = { name: string; enthusiasmLevel?: number };

function Hello({ name, enthusiasmLevel = 1 }: Props) {

if (enthusiasmLevel <= 0) {

throw new Error('You could be a little more enthusiastic. :D');

}

return <div>Hello {name + getExclamationMarks(enthusiasmLevel)}</div>;

}

The react repository provides more comprehensive TypeScript examples and explanations, focusing on best practices and common patterns. It serves as an extensive reference for developers of all levels. In contrast, TypeScript-React-Starter offers a complete project setup, making it easier for beginners to get started but with less depth in TypeScript specifics.

The complete guide to static typing in "React & Redux" apps using TypeScript

Pros of react-redux-typescript-guide

- More comprehensive coverage of Redux integration with TypeScript

- Includes advanced patterns and best practices for large-scale applications

- Provides detailed explanations and rationale for recommended approaches

Cons of react-redux-typescript-guide

- Less frequently updated compared to react

- May be overwhelming for beginners due to its depth and complexity

- Focuses more on Redux, which might not be necessary for all React projects

Code Comparison

react-redux-typescript-guide:

interface Props {

onClick(event: React.MouseEvent<HTMLElement>): void;

children?: React.ReactNode;

}

const Button: React.FC<Props> = ({ onClick: handleClick, children }) => (

<button onClick={handleClick}>{children}</button>

);

react:

type ButtonProps = {

onClick: () => void;

children: React.ReactNode;

};

const Button = ({ onClick, children }: ButtonProps) => (

<button onClick={onClick}>{children}</button>

);

The react-redux-typescript-guide example shows more specific typing for the event handler, while the react example is simpler but less type-specific. Both approaches are valid, with the choice depending on the level of type safety required and the complexity of the project.

Cheatsheets for experienced React developers getting started with TypeScript

Pros of react

- More comprehensive and detailed documentation

- Regularly updated with the latest TypeScript and React best practices

- Includes advanced topics and edge cases

Cons of react

- Can be overwhelming for beginners due to its depth

- May contain some outdated information in less frequently visited sections

Code Comparison

react:

interface Props {

name: string;

age: number;

}

const MyComponent: React.FC<Props> = ({ name, age }) => {

return <div>{`Hello, ${name}! You are ${age} years old.`}</div>;

};

react:

type Props = {

name: string;

age: number;

};

function MyComponent({ name, age }: Props) {

return <div>{`Hello, ${name}! You are ${age} years old.`}</div>;

}

Summary

Both repositories provide valuable TypeScript and React resources. react offers more extensive documentation and covers a wider range of topics, making it suitable for both beginners and advanced users. However, its depth can be overwhelming for newcomers. react, on the other hand, might be more approachable for beginners but may lack some of the advanced topics and detailed explanations found in react. The code examples show slight differences in typing approaches, with react using the React.FC type and react using a more concise function declaration.

The repository for high quality TypeScript type definitions.

Pros of DefinitelyTyped

- Comprehensive collection of type definitions for numerous JavaScript libraries and frameworks

- Large community of contributors, ensuring up-to-date and well-maintained type definitions

- Widely adopted and integrated into many development workflows and tools

Cons of DefinitelyTyped

- Can be overwhelming for beginners due to its vast scope and complexity

- May contain outdated or incorrect type definitions for less popular libraries

- Requires separate installation and management of type definitions

Code Comparison

DefinitelyTyped:

import * as React from 'react';

import { Button } from 'react-bootstrap';

const MyComponent: React.FC = () => {

return <Button variant="primary">Click me</Button>;

};

React TypeScript Cheatsheets:

import React from 'react';

const MyComponent: React.FC = () => {

return <button onClick={() => console.log('Clicked')}>Click me</button>;

};

The DefinitelyTyped example showcases type definitions for third-party libraries, while the React TypeScript Cheatsheets example focuses on React-specific TypeScript usage.

:sparkles: Monorepo for all the tooling which enables ESLint to support TypeScript

Pros of typescript-eslint

- Comprehensive linting and static analysis for TypeScript

- Highly configurable with numerous rules and plugins

- Actively maintained with frequent updates and improvements

Cons of typescript-eslint

- Steeper learning curve due to complex configuration options

- May require more setup time compared to simpler cheatsheets

- Can be overwhelming for beginners or small projects

Code Comparison

typescript-eslint configuration example:

{

"parser": "@typescript-eslint/parser",

"plugins": ["@typescript-eslint"],

"extends": [

"eslint:recommended",

"plugin:@typescript-eslint/recommended"

]

}

react cheatsheet example:

interface Props {

name: string;

age: number;

}

const MyComponent: React.FC<Props> = ({ name, age }) => {

return <div>{name} is {age} years old</div>;

};

typescript-eslint focuses on providing a powerful linting tool with extensive configuration options, while react offers concise, practical examples for using TypeScript with React. typescript-eslint is better suited for larger projects requiring strict code quality enforcement, whereas react is more accessible for developers looking to quickly reference TypeScript patterns in React applications.

Convert  designs to code with AI

designs to code with AI

Introducing Visual Copilot: A new AI model to turn Figma designs to high quality code using your components.

Try Visual CopilotREADME

React TypeScript Cheatsheet

Cheatsheet for using React with TypeScript.

Web docs | Contribute! | Ask!

:wave: This repo is maintained by @eps1lon and @filiptammergard. We're so happy you want to try out React with TypeScript! If you see anything wrong or missing, please file an issue! :+1:

- The Basic Cheatsheet is focused on helping React devs just start using TS in React apps

- Focus on opinionated best practices, copy+pastable examples.

- Explains some basic TS types usage and setup along the way.

- Answers the most Frequently Asked Questions.

- Does not cover generic type logic in detail. Instead we prefer to teach simple troubleshooting techniques for newbies.

- The goal is to get effective with TS without learning too much TS.

- The Advanced Cheatsheet helps show and explain advanced usage of generic types for people writing reusable type utilities/functions/render prop/higher order components and TS+React libraries.

- It also has miscellaneous tips and tricks for pro users.

- Advice for contributing to DefinitelyTyped.

- The goal is to take full advantage of TypeScript.

- The Migrating Cheatsheet helps collate advice for incrementally migrating large codebases from JS or Flow, from people who have done it.

- We do not try to convince people to switch, only to help people who have already decided.

- â ï¸This is a new cheatsheet, all assistance is welcome.

- The HOC Cheatsheet specifically teaches people to write HOCs with examples.

- Familiarity with Generics is necessary.

- â ï¸This is the newest cheatsheet, all assistance is welcome.

Basic Cheatsheet

Basic Cheatsheet Table of Contents

Expand Table of Contents

- React TypeScript Cheatsheet

- Basic Cheatsheet

- Basic Cheatsheet Table of Contents

- Section 1: Setup

- Section 2: Getting Started

- Function Components

- Hooks

- useState

- useCallback

- useReducer

- useEffect / useLayoutEffect

- useRef

- useImperativeHandle

- Custom Hooks

- More Hooks + TypeScript reading:

- Example React Hooks + TypeScript Libraries:

- Class Components

- Typing getDerivedStateFromProps

- You May Not Need

defaultProps - Typing

defaultProps - Consuming Props of a Component with defaultProps

- Misc Discussions and Knowledge

- Typing Component Props

- Basic Prop Types Examples

- Useful React Prop Type Examples

- Types or Interfaces?

- getDerivedStateFromProps

- Forms and Events

- Context

- Basic example

- Without default context value

- forwardRef/createRef

- Generic forwardRefs

- More Info

- Portals

- Error Boundaries

- Concurrent React/React Suspense

- Troubleshooting Handbook: Types

- Troubleshooting Handbook: Operators

- Troubleshooting Handbook: Utilities

- Troubleshooting Handbook: tsconfig.json

- Troubleshooting Handbook: Fixing bugs in official typings

- Troubleshooting Handbook: Globals, Images and other non-TS files

- Editor Tooling and Integration

- Linting

- Other React + TypeScript resources

- Recommended React + TypeScript talks

- Time to Really Learn TypeScript

- Example App

- My question isn't answered here!

- Contributors

- Basic Cheatsheet

Section 1: Setup

Prerequisites

You can use this cheatsheet for reference at any skill level, but basic understanding of React and TypeScript is assumed. Here is a list of prerequisites:

- Basic understanding of React.

- Familiarity with TypeScript Basics and Everyday Types.

In the cheatsheet we assume you are using the latest versions of React and TypeScript.

React and TypeScript starter kits

React has documentation for how to start a new React project with some of the most popular frameworks. Here's how to start them with TypeScript:

- Next.js:

npx create-next-app@latest --ts - Remix:

npx create-remix@latest - Gatsby:

npm init gatsby --ts - Expo:

npx create-expo-app -t with-typescript

Try React and TypeScript online

There are some tools that let you run React and TypeScript online, which can be helpful for debugging or making sharable reproductions.

Section 2: Getting Started

Function Components

These can be written as normal functions that take a props argument and return a JSX element.

// Declaring type of props - see "Typing Component Props" for more examples

type AppProps = {

message: string;

}; /* use `interface` if exporting so that consumers can extend */

// Easiest way to declare a Function Component; return type is inferred.

const App = ({ message }: AppProps) => <div>{message}</div>;

// You can choose to annotate the return type so an error is raised if you accidentally return some other type

const App = ({ message }: AppProps): React.JSX.Element => <div>{message}</div>;

// You can also inline the type declaration; eliminates naming the prop types, but looks repetitive

const App = ({ message }: { message: string }) => <div>{message}</div>;

// Alternatively, you can use `React.FunctionComponent` (or `React.FC`), if you prefer.

// With latest React types and TypeScript 5.1. it's mostly a stylistic choice, otherwise discouraged.

const App: React.FunctionComponent<{ message: string }> = ({ message }) => (

<div>{message}</div>

);

// or

const App: React.FC<AppProps> = ({ message }) => <div>{message}</div>;

Tip: You might use Paul Shen's VS Code Extension to automate the type destructure declaration (incl a keyboard shortcut).

Why is React.FC not needed? What about React.FunctionComponent/React.VoidFunctionComponent?

You may see this in many React+TypeScript codebases:

const App: React.FunctionComponent<{ message: string }> = ({ message }) => (

<div>{message}</div>

);

However, the general consensus today is that React.FunctionComponent (or the shorthand React.FC) is not needed. If you're still using React 17 or TypeScript lower than 5.1, it is even discouraged. This is a nuanced opinion of course, but if you agree and want to remove React.FC from your codebase, you can use this jscodeshift codemod.

Some differences from the "normal function" version:

-

React.FunctionComponentis explicit about the return type, while the normal function version is implicit (or else needs additional annotation). -

It provides typechecking and autocomplete for static properties like

displayName,propTypes, anddefaultProps.- Note that there are some known issues using

defaultPropswithReact.FunctionComponent. See this issue for details. We maintain a separatedefaultPropssection you can also look up.

- Note that there are some known issues using

-

Before the React 18 type updates,

React.FunctionComponentprovided an implicit definition ofchildren(see below), which was heavily debated and is one of the reasonsReact.FCwas removed from the Create React App TypeScript template.

// before React 18 types

const Title: React.FunctionComponent<{ title: string }> = ({

children,

title,

}) => <div title={title}>{children}</div>;

(Deprecated)Using React.VoidFunctionComponent or React.VFC instead

In @types/react 16.9.48, the React.VoidFunctionComponent or React.VFC type was added for typing children explicitly.

However, please be aware that React.VFC and React.VoidFunctionComponent were deprecated in React 18 (https://github.com/DefinitelyTyped/DefinitelyTyped/pull/59882), so this interim solution is no longer necessary or recommended in React 18+.

Please use regular function components or React.FC instead.

type Props = { foo: string };

// OK now, in future, error

const FunctionComponent: React.FunctionComponent<Props> = ({

foo,

children,

}: Props) => {

return (

<div>

{foo} {children}

</div>

); // OK

};

// Error now, in future, deprecated

const VoidFunctionComponent: React.VoidFunctionComponent<Props> = ({

foo,

children,

}) => {

return (

<div>

{foo}

{children}

</div>

);

};

- In the future, it may automatically mark props as

readonly, though that's a moot point if the props object is destructured in the parameter list.

In most cases it makes very little difference which syntax is used, but you may prefer the more explicit nature of React.FunctionComponent.

Hooks

Hooks are supported in @types/react from v16.8 up.

useState

Type inference works very well for simple values:

const [state, setState] = useState(false);

// `state` is inferred to be a boolean

// `setState` only takes booleans

See also the Using Inferred Types section if you need to use a complex type that you've relied on inference for.

However, many hooks are initialized with null-ish default values, and you may wonder how to provide types. Explicitly declare the type, and use a union type:

const [user, setUser] = useState<User | null>(null);

// later...

setUser(newUser);

You can also use type assertions if a state is initialized soon after setup and always has a value after:

const [user, setUser] = useState<User>({} as User);

// later...

setUser(newUser);

This temporarily "lies" to the TypeScript compiler that {} is of type User. You should follow up by setting the user state â if you don't, the rest of your code may rely on the fact that user is of type User and that may lead to runtime errors.

useCallback

You can type the useCallback just like any other function.

const memoizedCallback = useCallback(

(param1: string, param2: number) => {

console.log(param1, param2)

return { ok: true }

},

[...],

);

/**

* VSCode will show the following type:

* const memoizedCallback:

* (param1: string, param2: number) => { ok: boolean }

*/

Note that for React < 18, the function signature of useCallback typed arguments as any[] by default:

function useCallback<T extends (...args: any[]) => any>(

callback: T,

deps: DependencyList

): T;

In React >= 18, the function signature of useCallback changed to the following:

function useCallback<T extends Function>(callback: T, deps: DependencyList): T;

Therefore, the following code will yield "Parameter 'e' implicitly has an 'any' type." error in React >= 18, but not <17.

// @ts-expect-error Parameter 'e' implicitly has 'any' type.

useCallback((e) => {}, []);

// Explicit 'any' type.

useCallback((e: any) => {}, []);

useReducer

You can use Discriminated Unions for reducer actions. Don't forget to define the return type of reducer, otherwise TypeScript will infer it.

import { useReducer } from "react";

const initialState = { count: 0 };

type ACTIONTYPE =

| { type: "increment"; payload: number }

| { type: "decrement"; payload: string };

function reducer(state: typeof initialState, action: ACTIONTYPE) {

switch (action.type) {

case "increment":

return { count: state.count + action.payload };

case "decrement":

return { count: state.count - Number(action.payload) };

default:

throw new Error();

}

}

function Counter() {

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(reducer, initialState);

return (

<>

Count: {state.count}

<button onClick={() => dispatch({ type: "decrement", payload: "5" })}>

-

</button>

<button onClick={() => dispatch({ type: "increment", payload: 5 })}>

+

</button>

</>

);

}

View in the TypeScript Playground

Usage with Reducer from redux

In case you use the redux library to write reducer function, It provides a convenient helper of the format Reducer<State, Action> which takes care of the return type for you.

So the above reducer example becomes:

import { Reducer } from 'redux';

export function reducer: Reducer<AppState, Action>() {}

useEffect / useLayoutEffect

Both of useEffect and useLayoutEffect are used for performing side effects and return an optional cleanup function which means if they don't deal with returning values, no types are necessary. When using useEffect, take care not to return anything other than a function or undefined, otherwise both TypeScript and React will yell at you. This can be subtle when using arrow functions:

function DelayedEffect(props: { timerMs: number }) {

const { timerMs } = props;

useEffect(

() =>

setTimeout(() => {

/* do stuff */

}, timerMs),

[timerMs]

);

// bad example! setTimeout implicitly returns a number

// because the arrow function body isn't wrapped in curly braces

return null;

}

Solution to the above example

function DelayedEffect(props: { timerMs: number }) {

const { timerMs } = props;

useEffect(() => {

setTimeout(() => {

/* do stuff */

}, timerMs);

}, [timerMs]);

// better; use the void keyword to make sure you return undefined

return null;

}

useRef

In TypeScript, useRef returns a reference that is either read-only or mutable, depends on whether your type argument fully covers the initial value or not. Choose one that suits your use case.

Option 1: DOM element ref

To access a DOM element: provide only the element type as argument, and use null as initial value. In this case, the returned reference will have a read-only .current that is managed by React. TypeScript expects you to give this ref to an element's ref prop:

function Foo() {

// - If possible, prefer as specific as possible. For example, HTMLDivElement

// is better than HTMLElement and way better than Element.

// - Technical-wise, this returns RefObject<HTMLDivElement>

const divRef = useRef<HTMLDivElement>(null);

useEffect(() => {

// Note that ref.current may be null. This is expected, because you may

// conditionally render the ref-ed element, or you may forget to assign it

if (!divRef.current) throw Error("divRef is not assigned");

// Now divRef.current is sure to be HTMLDivElement

doSomethingWith(divRef.current);

});

// Give the ref to an element so React can manage it for you

return <div ref={divRef}>etc</div>;

}

If you are sure that divRef.current will never be null, it is also possible to use the non-null assertion operator !:

const divRef = useRef<HTMLDivElement>(null!);

// Later... No need to check if it is null

doSomethingWith(divRef.current);

Note that you are opting out of type safety here - you will have a runtime error if you forget to assign the ref to an element in the render, or if the ref-ed element is conditionally rendered.

Tip: Choosing which HTMLElement to use

Refs demand specificity - it is not enough to just specify any old HTMLElement. If you don't know the name of the element type you need, you can check lib.dom.ts or make an intentional type error and let the language service tell you:

Option 2: Mutable value ref

To have a mutable value: provide the type you want, and make sure the initial value fully belongs to that type:

function Foo() {

// Technical-wise, this returns MutableRefObject<number | null>

const intervalRef = useRef<number | null>(null);

// You manage the ref yourself (that's why it's called MutableRefObject!)

useEffect(() => {

intervalRef.current = setInterval(...);

return () => clearInterval(intervalRef.current);

}, []);

// The ref is not passed to any element's "ref" prop

return <button onClick={/* clearInterval the ref */}>Cancel timer</button>;

}

See also

useImperativeHandle

Based on this Stackoverflow answer:

// Countdown.tsx

// Define the handle types which will be passed to the forwardRef

export type CountdownHandle = {

start: () => void;

};

type CountdownProps = {};

const Countdown = forwardRef<CountdownHandle, CountdownProps>((props, ref) => {

useImperativeHandle(ref, () => ({

// start() has type inference here

start() {

alert("Start");

},

}));

return <div>Countdown</div>;

});

// The component uses the Countdown component

import Countdown, { CountdownHandle } from "./Countdown.tsx";

function App() {

const countdownEl = useRef<CountdownHandle>(null);

useEffect(() => {

if (countdownEl.current) {

// start() has type inference here as well

countdownEl.current.start();

}

}, []);

return <Countdown ref={countdownEl} />;

}

See also:

Custom Hooks

If you are returning an array in your Custom Hook, you will want to avoid type inference as TypeScript will infer a union type (when you actually want different types in each position of the array). Instead, use TS 3.4 const assertions:

import { useState } from "react";

export function useLoading() {

const [isLoading, setState] = useState(false);

const load = (aPromise: Promise<any>) => {

setState(true);

return aPromise.finally(() => setState(false));

};

return [isLoading, load] as const; // infers [boolean, typeof load] instead of (boolean | typeof load)[]

}

View in the TypeScript Playground

This way, when you destructure you actually get the right types based on destructure position.

Alternative: Asserting a tuple return type

If you are having trouble with const assertions, you can also assert or define the function return types:

import { useState } from "react";

export function useLoading() {

const [isLoading, setState] = useState(false);

const load = (aPromise: Promise<any>) => {

setState(true);

return aPromise.finally(() => setState(false));

};

return [isLoading, load] as [

boolean,

(aPromise: Promise<any>) => Promise<any>

];

}

A helper function that automatically types tuples can also be helpful if you write a lot of custom hooks:

function tuplify<T extends any[]>(...elements: T) {

return elements;

}

function useArray() {

const numberValue = useRef(3).current;

const functionValue = useRef(() => {}).current;

return [numberValue, functionValue]; // type is (number | (() => void))[]

}

function useTuple() {

const numberValue = useRef(3).current;

const functionValue = useRef(() => {}).current;

return tuplify(numberValue, functionValue); // type is [number, () => void]

}

Note that the React team recommends that custom hooks that return more than two values should use proper objects instead of tuples, however.

More Hooks + TypeScript reading:

- https://medium.com/@jrwebdev/react-hooks-in-typescript-88fce7001d0d

- https://fettblog.eu/typescript-react/hooks/#useref

If you are writing a React Hooks library, don't forget that you should also expose your types for users to use.

Example React Hooks + TypeScript Libraries:

- https://github.com/mweststrate/use-st8

- https://github.com/palmerhq/the-platform

- https://github.com/sw-yx/hooks

Something to add? File an issue.

Class Components

Within TypeScript, React.Component is a generic type (aka React.Component<PropType, StateType>), so you want to provide it with (optional) prop and state type parameters:

type MyProps = {

// using `interface` is also ok

message: string;

};

type MyState = {

count: number; // like this

};

class App extends React.Component<MyProps, MyState> {

state: MyState = {

// optional second annotation for better type inference

count: 0,

};

render() {

return (

<div>

{this.props.message} {this.state.count}

</div>

);

}

}

View in the TypeScript Playground

Don't forget that you can export/import/extend these types/interfaces for reuse.

Why annotate state twice?

It isn't strictly necessary to annotate the state class property, but it allows better type inference when accessing this.state and also initializing the state.

This is because they work in two different ways, the 2nd generic type parameter will allow this.setState() to work correctly, because that method comes from the base class, but initializing state inside the component overrides the base implementation so you have to make sure that you tell the compiler that you're not actually doing anything different.

No need for readonly

You often see sample code include readonly to mark props and state immutable:

type MyProps = {

readonly message: string;

};

type MyState = {

readonly count: number;

};

This is not necessary as React.Component<P,S> already marks them as immutable. (See PR and discussion!)

Class Methods: Do it like normal, but just remember any arguments for your functions also need to be typed:

class App extends React.Component<{ message: string }, { count: number }> {

state = { count: 0 };

render() {

return (

<div onClick={() => this.increment(1)}>

{this.props.message} {this.state.count}

</div>

);

}

increment = (amt: number) => {

// like this

this.setState((state) => ({

count: state.count + amt,

}));

};

}

View in the TypeScript Playground

Class Properties: If you need to declare class properties for later use, just declare it like state, but without assignment:

class App extends React.Component<{

message: string;

}> {

pointer: number; // like this

componentDidMount() {

this.pointer = 3;

}

render() {

return (

<div>

{this.props.message} and {this.pointer}

</div>

);

}

}

View in the TypeScript Playground

Something to add? File an issue.

Typing getDerivedStateFromProps

Before you start using getDerivedStateFromProps, please go through the documentation and You Probably Don't Need Derived State. Derived State can be implemented using hooks which can also help set up memoization.

Here are a few ways in which you can annotate getDerivedStateFromProps

- If you have explicitly typed your derived state and want to make sure that the return value from

getDerivedStateFromPropsconforms to it.

class Comp extends React.Component<Props, State> {

static getDerivedStateFromProps(

props: Props,

state: State

): Partial<State> | null {

//

}

}

- When you want the function's return value to determine your state.

class Comp extends React.Component<

Props,

ReturnType<typeof Comp["getDerivedStateFromProps"]>

> {

static getDerivedStateFromProps(props: Props) {}

}

- When you want derived state with other state fields and memoization

type CustomValue = any;

interface Props {

propA: CustomValue;

}

interface DefinedState {

otherStateField: string;

}

type State = DefinedState & ReturnType<typeof transformPropsToState>;

function transformPropsToState(props: Props) {

return {

savedPropA: props.propA, // save for memoization

derivedState: props.propA,

};

}

class Comp extends React.PureComponent<Props, State> {

constructor(props: Props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

otherStateField: "123",

...transformPropsToState(props),

};

}

static getDerivedStateFromProps(props: Props, state: State) {

if (isEqual(props.propA, state.savedPropA)) return null;

return transformPropsToState(props);

}

}

View in the TypeScript Playground

You May Not Need defaultProps

As per this tweet, defaultProps will eventually be deprecated. You can check the discussions here:

- Original tweet

- More info can also be found in this article

The consensus is to use object default values.

Function Components:

type GreetProps = { age?: number };

const Greet = ({ age = 21 }: GreetProps) => // etc

Class Components:

type GreetProps = {

age?: number;

};

class Greet extends React.Component<GreetProps> {

render() {

const { age = 21 } = this.props;

/*...*/

}

}

let el = <Greet age={3} />;

Typing defaultProps

Type inference improved greatly for defaultProps in TypeScript 3.0+, although some edge cases are still problematic.

Function Components

// using typeof as a shortcut; note that it hoists!

// you can also declare the type of DefaultProps if you choose

// e.g. https://github.com/typescript-cheatsheets/react/issues/415#issuecomment-841223219

type GreetProps = { age: number } & typeof defaultProps;

const defaultProps = {

age: 21,

};

const Greet = (props: GreetProps) => {

// etc

};

Greet.defaultProps = defaultProps;

For Class components, there are a couple ways to do it (including using the Pick utility type) but the recommendation is to "reverse" the props definition:

type GreetProps = typeof Greet.defaultProps & {

age: number;

};

class Greet extends React.Component<GreetProps> {

static defaultProps = {

age: 21,

};

/*...*/

}

// Type-checks! No type assertions needed!

let el = <Greet age={3} />;

React.JSX.LibraryManagedAttributes nuance for library authors

The above implementations work fine for App creators, but sometimes you want to be able to export GreetProps so that others can consume it. The problem here is that the way GreetProps is defined, age is a required prop when it isn't because of defaultProps.

The insight to have here is that GreetProps is the internal contract for your component, not the external, consumer facing contract. You could create a separate type specifically for export, or you could make use of the React.JSX.LibraryManagedAttributes utility:

// internal contract, should not be exported out

type GreetProps = {

age: number;

};

class Greet extends Component<GreetProps> {

static defaultProps = { age: 21 };

}

// external contract

export type ApparentGreetProps = React.JSX.LibraryManagedAttributes<

typeof Greet,

GreetProps

>;

This will work properly, although hovering overApparentGreetPropsmay be a little intimidating. You can reduce this boilerplate with theComponentProps utility detailed below.

Consuming Props of a Component with defaultProps

A component with defaultProps may seem to have some required props that actually aren't.

Problem Statement

Here's what you want to do:

interface IProps {

name: string;

}

const defaultProps = {

age: 25,

};

const GreetComponent = ({ name, age }: IProps & typeof defaultProps) => (

<div>{`Hello, my name is ${name}, ${age}`}</div>

);

GreetComponent.defaultProps = defaultProps;

const TestComponent = (props: React.ComponentProps<typeof GreetComponent>) => {

return <h1 />;

};

// Property 'age' is missing in type '{ name: string; }' but required in type '{ age: number; }'

const el = <TestComponent name="foo" />;

Solution

Define a utility that applies React.JSX.LibraryManagedAttributes:

type ComponentProps<T> = T extends

| React.ComponentType<infer P>

| React.Component<infer P>

? React.JSX.LibraryManagedAttributes<T, P>

: never;

const TestComponent = (props: ComponentProps<typeof GreetComponent>) => {

return <h1 />;

};

// No error

const el = <TestComponent name="foo" />;

Misc Discussions and Knowledge

Why does React.FC break defaultProps?

You can check the discussions here:

- https://medium.com/@martin_hotell/10-typescript-pro-tips-patterns-with-or-without-react-5799488d6680

- https://github.com/DefinitelyTyped/DefinitelyTyped/issues/30695

- https://github.com/typescript-cheatsheets/react/issues/87

This is just the current state and may be fixed in future.

TypeScript 2.9 and earlier

For TypeScript 2.9 and earlier, there's more than one way to do it, but this is the best advice we've yet seen:

type Props = Required<typeof MyComponent.defaultProps> & {

/* additional props here */

};

export class MyComponent extends React.Component<Props> {

static defaultProps = {

foo: "foo",

};

}

Our former recommendation used the Partial type feature in TypeScript, which means that the current interface will fulfill a partial version on the wrapped interface. In that way we can extend defaultProps without any changes in the types!

interface IMyComponentProps {

firstProp?: string;

secondProp: IPerson[];

}

export class MyComponent extends React.Component<IMyComponentProps> {

public static defaultProps: Partial<IMyComponentProps> = {

firstProp: "default",

};

}

The problem with this approach is it causes complex issues with the type inference working with React.JSX.LibraryManagedAttributes. Basically it causes the compiler to think that when creating a JSX expression with that component, that all of its props are optional.

Something to add? File an issue.

Typing Component Props

This is intended as a basic orientation and reference for React developers familiarizing with TypeScript.

Basic Prop Types Examples

A list of TypeScript types you will likely use in a React+TypeScript app:

type AppProps = {

message: string;

count: number;

disabled: boolean;

/** array of a type! */

names: string[];

/** string literals to specify exact string values, with a union type to join them together */

status: "waiting" | "success";

/** an object with known properties (but could have more at runtime) */

obj: {

id: string;

title: string;

};

/** array of objects! (common) */

objArr: {

id: string;

title: string;

}[];

/** any non-primitive value - can't access any properties (NOT COMMON but useful as placeholder) */

obj2: object;

/** an interface with no required properties - (NOT COMMON, except for things like `React.Component<{}, State>`) */

obj3: {};

/** a dict object with any number of properties of the same type */

dict1: {

[key: string]: MyTypeHere;

};

dict2: Record<string, MyTypeHere>; // equivalent to dict1

/** function that doesn't take or return anything (VERY COMMON) */

onClick: () => void;

/** function with named prop (VERY COMMON) */

onChange: (id: number) => void;

/** function type syntax that takes an event (VERY COMMON) */

onChange: (event: React.ChangeEvent<HTMLInputElement>) => void;

/** alternative function type syntax that takes an event (VERY COMMON) */

onClick(event: React.MouseEvent<HTMLButtonElement>): void;

/** any function as long as you don't invoke it (not recommended) */

onSomething: Function;

/** an optional prop (VERY COMMON!) */

optional?: OptionalType;

/** when passing down the state setter function returned by `useState` to a child component. `number` is an example, swap out with whatever the type of your state */

setState: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<number>>;

};

object as the non-primitive type

object is a common source of misunderstanding in TypeScript. It does not mean "any object" but rather "any non-primitive type", which means it represents anything that is not number, bigint, string, boolean, symbol, null or undefined.

Typing "any non-primitive value" is most likely not something that you should do much in React, which means you will probably not use object much.

Empty interface, {} and Object

An empty interface, {} and Object all represent "any non-nullish value"ânot "an empty object" as you might think. Using these types is a common source of misunderstanding and is not recommended.

interface AnyNonNullishValue {} // equivalent to `type AnyNonNullishValue = {}` or `type AnyNonNullishValue = Object`

let value: AnyNonNullishValue;

// these are all fine, but might not be expected

value = 1;

value = "foo";

value = () => alert("foo");

value = {};

value = { foo: "bar" };

// these are errors

value = undefined;

value = null;

Useful React Prop Type Examples

Relevant for components that accept other React components as props.

export declare interface AppProps {

children?: React.ReactNode; // best, accepts everything React can render

childrenElement: React.JSX.Element; // A single React element

style?: React.CSSProperties; // to pass through style props

onChange?: React.FormEventHandler<HTMLInputElement>; // form events! the generic parameter is the type of event.target

// more info: https://react-typescript-cheatsheet.netlify.app/docs/advanced/patterns_by_usecase/#wrappingmirroring

props: Props & React.ComponentPropsWithoutRef<"button">; // to impersonate all the props of a button element and explicitly not forwarding its ref

props2: Props & React.ComponentPropsWithRef<MyButtonWithForwardRef>; // to impersonate all the props of MyButtonForwardedRef and explicitly forwarding its ref

}

Small React.ReactNode edge case before React 18

Before the React 18 type updates, this code typechecked but had a runtime error:

type Props = {

children?: React.ReactNode;

};

function Comp({ children }: Props) {

return <div>{children}</div>;

}

function App() {

// Before React 18: Runtime error "Objects are not valid as a React child"

// After React 18: Typecheck error "Type '{}' is not assignable to type 'ReactNode'"

return <Comp>{{}}</Comp>;

}

This is because ReactNode includes ReactFragment which allowed type {} before React 18.

React.JSX.Element vs React.ReactNode?

Quote @ferdaber: A more technical explanation is that a valid React node is not the same thing as what is returned by React.createElement. Regardless of what a component ends up rendering, React.createElement always returns an object, which is the React.JSX.Element interface, but React.ReactNode is the set of all possible return values of a component.

React.JSX.Element-> Return value ofReact.createElementReact.ReactNode-> Return value of a component

More discussion: Where ReactNode does not overlap with React.JSX.Element

Something to add? File an issue.

Types or Interfaces?

You can use either Types or Interfaces to type Props and State, so naturally the question arises - which do you use?

TL;DR

Use Interface until You Need Type - orta.

More Advice

Here's a helpful rule of thumb:

-

always use

interfacefor public API's definition when authoring a library or 3rd party ambient type definitions, as this allows a consumer to extend them via declaration merging if some definitions are missing. -

consider using

typefor your React Component Props and State, for consistency and because it is more constrained.

You can read more about the reasoning behind this rule of thumb in Interface vs Type alias in TypeScript 2.7.

The TypeScript Handbook now also includes guidance on Differences Between Type Aliases and Interfaces.

Note: At scale, there are performance reasons to prefer interfaces (see official Microsoft notes on this) but take this with a grain of salt

Types are useful for union types (e.g. type MyType = TypeA | TypeB) whereas Interfaces are better for declaring dictionary shapes and then implementing or extending them.

Useful table for Types vs Interfaces

It's a nuanced topic, don't get too hung up on it. Here's a handy table:

| Aspect | Type | Interface |

|---|---|---|

| Can describe functions | â | â |

| Can describe constructors | â | â |

| Can describe tuples | â | â |

| Interfaces can extend it | â ï¸ | â |

| Classes can extend it | ð« | â |

Classes can implement it (implements) | â ï¸ | â |

| Can intersect another one of its kind | â | â ï¸ |

| Can create a union with another one of its kind | â | ð« |

| Can be used to create mapped types | â | ð« |

| Can be mapped over with mapped types | â | â |

| Expands in error messages and logs | â | ð« |

| Can be augmented | ð« | â |

| Can be recursive | â ï¸ | â |

â ï¸ In some cases

(source: Karol Majewski)

Something to add? File an issue.

getDerivedStateFromProps

Before you start using getDerivedStateFromProps, please go through the documentation and You Probably Don't Need Derived State. Derived State can be easily achieved using hooks which can also help set up memoization easily.

Here are a few ways in which you can annotate getDerivedStateFromProps

- If you have explicitly typed your derived state and want to make sure that the return value from

getDerivedStateFromPropsconforms to it.

class Comp extends React.Component<Props, State> {

static getDerivedStateFromProps(

props: Props,

state: State

): Partial<State> | null {

//

}

}

- When you want the function's return value to determine your state.

class Comp extends React.Component<

Props,

ReturnType<typeof Comp["getDerivedStateFromProps"]>

> {

static getDerivedStateFromProps(props: Props) {}

}

- When you want derived state with other state fields and memoization

type CustomValue = any;

interface Props {

propA: CustomValue;

}

interface DefinedState {

otherStateField: string;

}

type State = DefinedState & ReturnType<typeof transformPropsToState>;

function transformPropsToState(props: Props) {

return {

savedPropA: props.propA, // save for memoization

derivedState: props.propA,

};

}

class Comp extends React.PureComponent<Props, State> {

constructor(props: Props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

otherStateField: "123",

...transformPropsToState(props),

};

}

static getDerivedStateFromProps(props: Props, state: State) {

if (isEqual(props.propA, state.savedPropA)) return null;

return transformPropsToState(props);

}

}

View in the TypeScript Playground

Forms and Events

If performance is not an issue (and it usually isn't!), inlining handlers is easiest as you can just use type inference and contextual typing:

const el = (

<button

onClick={(event) => {

/* event will be correctly typed automatically! */

}}

/>

);

But if you need to define your event handler separately, IDE tooling really comes in handy here, as the @type definitions come with a wealth of typing. Type what you are looking for and usually the autocomplete will help you out. Here is what it looks like for an onChange for a form event:

type State = {

text: string;

};

class App extends React.Component<Props, State> {

state = {

text: "",

};

// typing on RIGHT hand side of =

onChange = (e: React.FormEvent<HTMLInputElement>): void => {

this.setState({ text: e.currentTarget.value });

};

render() {

return (

<div>

<input type="text" value={this.state.text} onChange={this.onChange} />

</div>

);

}

}

View in the TypeScript Playground

Instead of typing the arguments and return values with React.FormEvent<> and void, you may alternatively apply types to the event handler itself (contributed by @TomasHubelbauer):

// typing on LEFT hand side of =

onChange: React.ChangeEventHandler<HTMLInputElement> = (e) => {

this.setState({text: e.currentTarget.value})

}

Why two ways to do the same thing?

The first method uses an inferred method signature (e: React.FormEvent<HTMLInputElement>): void and the second method enforces a type of the delegate provided by @types/react. So React.ChangeEventHandler<> is simply a "blessed" typing by @types/react, whereas you can think of the inferred method as more... artisanally hand-rolled. Either way it's a good pattern to know. See our Github PR for more.

Typing onSubmit, with Uncontrolled components in a Form

If you don't quite care about the type of the event, you can just use React.SyntheticEvent. If your target form has custom named inputs that you'd like to access, you can use a type assertion:

<form

ref={formRef}

onSubmit={(e: React.SyntheticEvent) => {

e.preventDefault();

const target = e.target as typeof e.target & {

email: { value: string };

password: { value: string };

};

const email = target.email.value; // typechecks!

const password = target.password.value; // typechecks!

// etc...

}}

>

<div>

<label>

Email:

<input type="email" name="email" />

</label>

</div>

<div>

<label>

Password:

<input type="password" name="password" />

</label>

</div>

<div>

<input type="submit" value="Log in" />

</div>

</form>

View in the TypeScript Playground

Of course, if you're making any sort of significant form, you should use Formik or React Hook Form, which are written in TypeScript.

List of event types

| Event Type | Description |

|---|---|

| AnimationEvent | CSS Animations. |

| ChangeEvent | Changing the value of <input>, <select> and <textarea> element. |

| ClipboardEvent | Using copy, paste and cut events. |

| CompositionEvent | Events that occur due to the user indirectly entering text (e.g. depending on Browser and PC setup, a popup window may appear with additional characters if you e.g. want to type Japanese on a US Keyboard) |

| DragEvent | Drag and drop interaction with a pointer device (e.g. mouse). |

| FocusEvent | Event that occurs when elements gets or loses focus. |

| FormEvent | Event that occurs whenever a form or form element gets/loses focus, a form element value is changed or the form is submitted. |

| InvalidEvent | Fired when validity restrictions of an input fails (e.g <input type="number" max="10"> and someone would insert number 20). |

| KeyboardEvent | User interaction with the keyboard. Each event describes a single key interaction. |

| InputEvent | Event that occurs before the value of <input>, <select> and <textarea> changes. |

| MouseEvent | Events that occur due to the user interacting with a pointing device (e.g. mouse) |

| PointerEvent | Events that occur due to user interaction with a variety pointing of devices such as mouse, pen/stylus, a touchscreen and which also supports multi-touch. Unless you develop for older browsers (IE10 or Safari 12), pointer events are recommended. Extends UIEvent. |

| TouchEvent | Events that occur due to the user interacting with a touch device. Extends UIEvent. |

| TransitionEvent | CSS Transition. Not fully browser supported. Extends UIEvent |

| UIEvent | Base Event for Mouse, Touch and Pointer events. |

| WheelEvent | Scrolling on a mouse wheel or similar input device. (Note: wheel event should not be confused with the scroll event) |

| SyntheticEvent | The base event for all above events. Should be used when unsure about event type |

Context

Basic example

Here's a basic example of creating a context containing the active theme.

import { createContext } from "react";

type ThemeContextType = "light" | "dark";

const ThemeContext = createContext<ThemeContextType>("light");

Wrap the components that need the context with a context provider:

import { useState } from "react";

const App = () => {

const [theme, setTheme] = useState<ThemeContextType>("light");

return (

<ThemeContext.Provider value={theme}>

<MyComponent />

</ThemeContext.Provider>

);

};

Call useContext to read and subscribe to the context.

import { useContext } from "react";

const MyComponent = () => {

const theme = useContext(ThemeContext);

return <p>The current theme is {theme}.</p>;

};

Without default context value

If you don't have any meaningful default value, specify null:

import { createContext } from "react";

interface CurrentUserContextType {

username: string;

}

const CurrentUserContext = createContext<CurrentUserContextType | null>(null);

const App = () => {

const [currentUser, setCurrentUser] = useState<CurrentUserContextType>({

username: "filiptammergard",

});

return (

<CurrentUserContext.Provider value={currentUser}>

<MyComponent />

</CurrentUserContext.Provider>

);

};

Now that the type of the context can be null, you'll notice that you'll get a 'currentUser' is possibly 'null' TypeScript error if you try to access the username property. You can use optional chaining to access username:

import { useContext } from "react";

const MyComponent = () => {

const currentUser = useContext(CurrentUserContext);

return <p>Name: {currentUser?.username}.</p>;

};

However, it would be preferable to not have to check for null, since we know that the context won't be null. One way to do that is to provide a custom hook to use the context, where an error is thrown if the context is not provided:

import { createContext } from "react";

interface CurrentUserContextType {

username: string;

}

const CurrentUserContext = createContext<CurrentUserContextType | null>(null);

const useCurrentUser = () => {

const currentUserContext = useContext(CurrentUserContext);

if (!currentUserContext) {

throw new Error(

"useCurrentUser has to be used within <CurrentUserContext.Provider>"

);

}

return currentUserContext;

};

Using a runtime type check in this will has the benefit of printing a clear error message in the console when a provider is not wrapping the components properly. Now it's possible to access currentUser.username without checking for null:

import { useContext } from "react";

const MyComponent = () => {

const currentUser = useCurrentUser();

return <p>Username: {currentUser.username}.</p>;

};

Type assertion as an alternative

Another way to avoid having to check for null is to use type assertion to tell TypeScript you know the context is not null:

import { useContext } from "react";

const MyComponent = () => {

const currentUser = useContext(CurrentUserContext);

return <p>Name: {currentUser!.username}.</p>;

};

Another option is to use an empty object as default value and cast it to the expected context type:

const CurrentUserContext = createContext<CurrentUserContextType>(

{} as CurrentUserContextType

);

You can also use non-null assertion to get the same result:

const CurrentUserContext = createContext<CurrentUserContextType>(null!);

When you don't know what to choose, prefer runtime checking and throwing over type asserting.

forwardRef/createRef

For useRef, check the Hooks section.

Ref as a Prop (Recommended for React 19+)

In React 19+, you can access ref directly as a prop in function components - no forwardRef wrapper needed.

Option 1: Inherit all props from a native element

Use ComponentPropsWithRef to inherit all props from a native element.

import { ComponentPropsWithRef, useRef } from "react";

function MyInput(props: ComponentPropsWithRef<"input">) {

return <input {...props} />;

}

// Usage in parent component

function Parent() {

const inputRef = useRef<HTMLInputElement>(null);

return <MyInput ref={inputRef} placeholder="Type here..." />;

}

Option 2: Explicit typing

If you have custom props and want fine-grained control, you can explicitly type the ref:

import { Ref, useRef } from "react";

interface MyInputProps {

placeholder: string;

ref: Ref<HTMLInputElement>;

}

function MyInput(props: MyInputProps) {

return <input {...props} />;

}

// Usage in parent component

function Parent() {

const inputRef = useRef<HTMLInputElement>(null);

return <MyInput ref={inputRef} placeholder="Type here..." />;

}

Read more: Wrapping/Mirroring a HTML Element

Legacy Approaches (Pre-React 19)

forwardRef

For React 18 and earlier, use forwardRef:

import { forwardRef, ReactNode } from "react";

interface Props {

children?: ReactNode;

type: "submit" | "button";

}

export type Ref = HTMLButtonElement;

export const FancyButton = forwardRef<Ref, Props>((props, ref) => (

<button ref={ref} className="MyClassName" type={props.type}>

{props.children}

</button>

));

Side note: the ref you get from forwardRef is mutable so you can assign to it if needed.

This was done on purpose. You can make it immutable if you have to - assign React.Ref if you want to ensure nobody reassigns it:

import { forwardRef, ReactNode, Ref } from "react";

interface Props {

children?: ReactNode;

type: "submit" | "button";

}

export const FancyButton = forwardRef(

(

props: Props,

ref: Ref<HTMLButtonElement> // <-- explicit immutable ref type

) => (

<button ref={ref} className="MyClassName" type={props.type}>

{props.children}

</button>

)

);

If you need to grab props from a component that forwards refs, use ComponentPropsWithRef.

createRef

createRef is mostly used for class components. Function components typically rely on useRef instead.

import { createRef, PureComponent } from "react";

class CssThemeProvider extends PureComponent<Props> {

private rootRef = createRef<HTMLDivElement>();

render() {

return <div ref={this.rootRef}>{this.props.children}</div>;

}

}

Generic Components with Refs

Generic components typically require manual ref handling since their generic nature prevents automatic type inference. Here are the main approaches:

Read more context in this article.

Option 1: Wrapper Component

The most straightforward approach is to manually handle refs through props:

interface ClickableListProps<T> {

items: T[];

onSelect: (item: T) => void;

mRef?: React.Ref<HTMLUListElement> | null;

}

export function ClickableList<T>(props: ClickableListProps<T>) {

return (

<ul ref={props.mRef}>

{props.items.map((item, i) => (

<li key={i}>

<button onClick={() => props.onSelect(item)}>Select</button>

{item}

</li>

))}

</ul>

);

}

Option 2: Redeclare forwardRef

For true forwardRef behavior with generics, extend the module declaration:

// Redeclare forwardRef to support generics

declare module "react" {

function forwardRef<T, P = {}>(

render: (props: P, ref: React.Ref<T>) => React.ReactElement | null

): (props: P & React.RefAttributes<T>) => React.ReactElement | null;

}

// Now you can use forwardRef with generics normally

import { forwardRef, ForwardedRef } from "react";

interface ClickableListProps<T> {

items: T[];

onSelect: (item: T) => void;

}

function ClickableListInner<T>(

props: ClickableListProps<T>,

ref: ForwardedRef<HTMLUListElement>

) {

return (

<ul ref={ref}>

{props.items.map((item, i) => (

<li key={i}>

<button onClick={() => props.onSelect(item)}>Select</button>

{item}

</li>

))}

</ul>

);

}

export const ClickableList = forwardRef(ClickableListInner);

Option 3: Call Signature

If you need both generic support and proper forwardRef behavior with full type inference, you can use the call signature:

// Add to your type definitions (e.g. in `index.d.ts` file)

interface ForwardRefWithGenerics extends React.FC<WithForwardRefProps<Option>> {

<T extends Option>(props: WithForwardRefProps<T>): ReturnType<

React.FC<WithForwardRefProps<T>>

>;

}

export const ClickableListWithForwardRef: ForwardRefWithGenerics =

forwardRef(ClickableList);

Credits: https://stackoverflow.com/a/73795494

:::note

Option 1 is usually sufficient and clearer. Use Option 2 when you specifically need forwardRef behavior. Use Option 3 for advanced library scenarios requiring both generics and full forwardRef type inference.

:::

Additional Resources

Something to add? File an issue

Portals

Using ReactDOM.createPortal:

const modalRoot = document.getElementById("modal-root") as HTMLElement;

// assuming in your html file has a div with id 'modal-root';

export class Modal extends React.Component<{ children?: React.ReactNode }> {

el: HTMLElement = document.createElement("div");

componentDidMount() {

modalRoot.appendChild(this.el);

}

componentWillUnmount() {

modalRoot.removeChild(this.el);

}

render() {

return ReactDOM.createPortal(this.props.children, this.el);

}

}

View in the TypeScript Playground

Using hooks

Same as above but using hooks

import { useEffect, useRef, ReactNode } from "react";

import { createPortal } from "react-dom";

const modalRoot = document.querySelector("#modal-root") as HTMLElement;

type ModalProps = {

children: ReactNode;

};

function Modal({ children }: ModalProps) {

// create div element only once using ref

const elRef = useRef<HTMLDivElement | null>(null);

if (!elRef.current) elRef.current = document.createElement("div");

useEffect(() => {

const el = elRef.current!; // non-null assertion because it will never be null

modalRoot.appendChild(el);

return () => {

modalRoot.removeChild(el);

};

}, []);

return createPortal(children, elRef.current);

}

Modal Component Usage Example:

import { useState } from "react";

function App() {

const [showModal, setShowModal] = useState(false);

return (

<div>

// you can also put this in your static html file

<div id="modal-root"></div>

{showModal && (

<Modal>

<div

style={{

display: "grid",

placeItems: "center",

height: "100vh",

width: "100vh",

background: "rgba(0,0,0,0.1)",

zIndex: 99,

}}

>

I'm a modal!{" "}

<button

style={{ background: "papyawhip" }}

onClick={() => setShowModal(false)}

>

close

</button>

</div>

</Modal>

)}

<button onClick={() => setShowModal(true)}>show Modal</button>

// rest of your app

</div>

);

}

Context of Example

This example is based on the Event Bubbling Through Portal example of React docs.

Error Boundaries

Option 1: Using react-error-boundary

React-error-boundary - is a lightweight package ready to use for this scenario with TS support built-in. This approach also lets you avoid class components that are not that popular anymore.

Option 2: Writing your custom error boundary component

If you don't want to add a new npm package for this, you can also write your own ErrorBoundary component.

import React, { Component, ErrorInfo, ReactNode } from "react";

interface Props {

children?: ReactNode;

}

interface State {

hasError: boolean;

}

class ErrorBoundary extends Component<Props, State> {

public state: State = {

hasError: false

};

public static getDerivedStateFromError(_: Error): State {

// Update state so the next render will show the fallback UI.

return { hasError: true };

}

public componentDidCatch(error: Error, errorInfo: ErrorInfo) {

console.error("Uncaught error:", error, errorInfo);

}

public render() {

if (this.state.hasError) {

return <h1>Sorry.. there was an error</h1>;

}

return this.props.children;

}

}

export default ErrorBoundary;

Something to add? File an issue.

Concurrent React/React Suspense

Not written yet. watch https://github.com/sw-yx/fresh-async-react for more on React Suspense and Time Slicing.

Something to add? File an issue.

Troubleshooting Handbook: Types

â ï¸ Have you read the TypeScript FAQ Your answer might be there!

Facing weird type errors? You aren't alone. This is the hardest part of using TypeScript with React. Be patient - you are learning a new language after all. However, the more you get good at this, the less time you'll be working against the compiler and the more the compiler will be working for you!

Try to avoid typing with any as much as possible to experience the full benefits of TypeScript. Instead, let's try to be familiar with some of the common strategies to solve these issues.

Union Types and Type Guarding

Union types are handy for solving some of these typing problems:

class App extends React.Component<

{},

{

count: number | null; // like this

}

> {

state = {

count: null,

};

render() {

return <div onClick={() => this.increment(1)}>{this.state.count}</div>;

}

increment = (amt: number) => {

this.setState((state) => ({

count: (state.count || 0) + amt,

}));

};

}

View in the TypeScript Playground

Type Guarding: Sometimes Union Types solve a problem in one area but create another downstream. If A and B are both object types, A | B isn't "either A or B", it is "A or B or both at once", which causes some confusion if you expected it to be the former. Learn how to write checks, guards, and assertions (also see the Conditional Rendering section below). For example:

interface Admin {

role: string;

}

interface User {

email: string;

}

// Method 1: use `in` keyword

function redirect(user: Admin | User) {

if ("role" in user) {

// use the `in` operator for typeguards since TS 2.7+

routeToAdminPage(user.role);

} else {

routeToHomePage(user.email);

}

}

// Method 2: custom type guard, does the same thing in older TS versions or where `in` isnt enough

function isAdmin(user: Admin | User): user is Admin {

return (user as any).role !== undefined;

}

View in the TypeScript Playground

Method 2 is also known as User-Defined Type Guards and can be really handy for readable code. This is how TS itself refines types with typeof and instanceof.

If you need if...else chains or the switch statement instead, it should "just work", but look up Discriminated Unions if you need help. (See also: Basarat's writeup). This is handy in typing reducers for useReducer or Redux.

Optional Types

If a component has an optional prop, add a question mark and assign during destructure (or use defaultProps).

class MyComponent extends React.Component<{

message?: string; // like this

}> {

render() {

const { message = "default" } = this.props;

return <div>{message}</div>;

}

}

You can also use a ! character to assert that something is not undefined, but this is not encouraged.

Something to add? File an issue with your suggestions!

Enum Types

We recommend avoiding using enums as far as possible.

Enums have a few documented issues (the TS team agrees). A simpler alternative to enums is just declaring a union type of string literals:

export declare type Position = "left" | "right" | "top" | "bottom";

If you must use enums, remember that enums in TypeScript default to numbers. You will usually want to use them as strings instead:

export enum ButtonSizes {

default = "default",

small = "small",

large = "large",

}

// usage

export const PrimaryButton = (

props: Props & React.HTMLProps<HTMLButtonElement>

) => <Button size={ButtonSizes.default} {...props} />;

Type Assertion

Sometimes you know better than TypeScript that the type you're using is narrower than it thinks, or union types need to be asserted to a more specific type to work with other APIs, so assert with the as keyword. This tells the compiler you know better than it does.

class MyComponent extends React.Component<{

message: string;

}> {

render() {

const { message } = this.props;

return (

<Component2 message={message as SpecialMessageType}>{message}</Component2>

);

}

}

View in the TypeScript Playground

Note that you cannot assert your way to anything - basically it is only for refining types. Therefore it is not the same as "casting" a type.

You can also assert a property is non-null, when accessing it:

element.parentNode!.removeChild(element); // ! before the period

myFunction(document.getElementById(dialog.id!)!); // ! after the property accessing

let userID!: string; // definite assignment assertion... be careful!

Of course, try to actually handle the null case instead of asserting :)

Simulating Nominal Types

TS' structural typing is handy, until it is inconvenient. However you can simulate nominal typing with type branding:

type OrderID = string & { readonly brand: unique symbol };

type UserID = string & { readonly brand: unique symbol };

type ID = OrderID | UserID;

We can create these values with the Companion Object Pattern:

function OrderID(id: string) {

return id as OrderID;

}

function UserID(id: string) {

return id as UserID;

}

Now TypeScript will disallow you from using the wrong ID in the wrong place:

function queryForUser(id: UserID) {

// ...

}

queryForUser(OrderID("foobar")); // Error, Argument of type 'OrderID' is not assignable to parameter of type 'UserID'

In future you can use the unique keyword to brand. See this PR.

Intersection Types

Adding two types together can be handy, for example when your component is supposed to mirror the props of a native component like a button:

export interface PrimaryButtonProps {

label: string;

}

export const PrimaryButton = (

props: PrimaryButtonProps & React.ButtonHTMLAttributes<HTMLButtonElement>

) => {

// do custom buttony stuff

return <button {...props}> {props.label} </button>;

};

Playground here

You can also use Intersection Types to make reusable subsets of props for similar components:

type BaseProps = {

className?: string,

style?: React.CSSProperties

name: string // used in both

}

type DogProps = {

tailsCount: number

}

type HumanProps = {

handsCount: number

}

export const Human = (props: BaseProps & HumanProps) => // ...

export const Dog = (props: BaseProps & DogProps) => // ...

View in the TypeScript Playground

Make sure not to confuse Intersection Types (which are and operations) with Union Types (which are or operations).

Union Types

This section is yet to be written (please contribute!). Meanwhile, see our commentary on Union Types usecases.

The ADVANCED cheatsheet also has information on Discriminated Union Types, which are helpful when TypeScript doesn't seem to be narrowing your union type as you expect.

Overloading Function Types

Specifically when it comes to functions, you may need to overload instead of union type. The most common way function types are written uses the shorthand:

type FunctionType1 = (x: string, y: number) => number;

But this doesn't let you do any overloading. If you have the implementation, you can put them after each other with the function keyword:

function pickCard(x: { suit: string; card: number }[]): number;

function pickCard(x: number): { suit: string; card: number };

function pickCard(x): any {

// implementation with combined signature

// ...

}

However, if you don't have an implementation and are just writing a .d.ts definition file, this won't help you either. In this case you can forego any shorthand and write them the old-school way. The key thing to remember here is as far as TypeScript is concerned, functions are just callable objects with no key:

type pickCard = {

(x: { suit: string; card: number }[]): number;

(x: number): { suit: string; card: number };

// no need for combined signature in this form

// you can also type static properties of functions here eg `pickCard.wasCalled`

};

Note that when you implement the actual overloaded function, the implementation will need to declare the combined call signature that you'll be handling, it won't be inferred for you. You can readily see examples of overloads in DOM APIs, e.g. createElement.

Read more about Overloading in the Handbook.

Using Inferred Types

Leaning on TypeScript's Type Inference is great... until you realize you need a type that was inferred, and have to go back and explicitly declare types/interfaces so you can export them for reuse.

Fortunately, with typeof, you won't have to do that. Just use it on any value:

const [state, setState] = useState({

foo: 1,

bar: 2,

}); // state's type inferred to be {foo: number, bar: number}

const someMethod = (obj: typeof state) => {

// grabbing the type of state even though it was inferred

// some code using obj

setState(obj); // this works

};

Using Partial Types

Working with slicing state and props is common in React. Again, you don't really have to go and explicitly redefine your types if you use the Partial generic type:

const [state, setState] = useState({

foo: 1,

bar: 2,

}); // state's type inferred to be {foo: number, bar: number}

// NOTE: stale state merging is not actually encouraged in useState

// we are just demonstrating how to use Partial here

const partialStateUpdate = (obj: Partial<typeof state>) =>

setState({ ...state, ...obj });

// later on...

partialStateUpdate({ foo: 2 }); // this works

Minor caveats on using Partial

Note that there are some TS users who don't agree with using Partial as it behaves today. See subtle pitfalls of the above example here, and check out this long discussion on why @types/react uses Pick instead of Partial.

The Types I need weren't exported!

This can be annoying but here are ways to grab the types!

- Grabbing the Prop types of a component: Use

React.ComponentPropsandtypeof, and optionallyOmitany overlapping types

import { Button } from "library"; // but doesn't export ButtonProps! oh no!

type ButtonProps = React.ComponentProps<typeof Button>; // no problem! grab your own!

type AlertButtonProps = Omit<ButtonProps, "onClick">; // modify

const AlertButton = (props: AlertButtonProps) => (

<Button onClick={() => alert("hello")} {...props} />

);